Historical Background and the Evolution of Negotiations

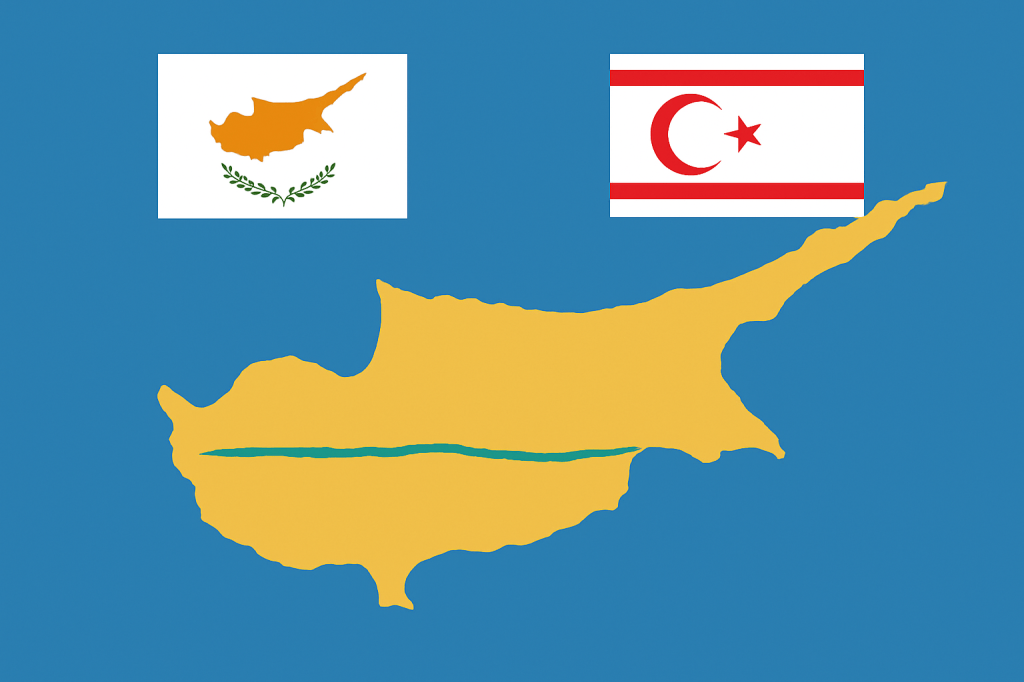

Although the Republic of Cyprus was established in 1960 as a bi-communal partnership state, this arrangement did not last long. In 1963, following unilateral attempts by the Greek Cypriot leadership to amend the constitution and the eruption of armed clashes known as Bloody Christmas, the partnership state effectively collapsed; Turkish Cypriots were excluded from state institutions. The island-wide escalation of violence and Greece’s interventions aimed at Enosis (union with Greece) laid the groundwork for Turkey’s intervention. On 15 July 1974, when the Greek junta in Greece staged a coup in Cyprus and Makarios was overthrown in an attempt to declare Enosis, Turkey launched a military operation on 20 July 1974, invoking the Treaty of Guarantee. As a result of the Cyprus Peace Operation, which took place in two phases, 37% of the island came under Turkish control and the current de facto boundaries were drawn. Subsequently, under UN supervision, a population exchange was implemented in 1975, whereby Turks were concentrated in the north and Greeks in the south; approximately 120,000 Greek Cypriots resettled in the south and 65,000 Turkish Cypriots in the north. This separation laid the foundations for the two separate administrations on the island.

After 1974, efforts to resolve the Cyprus issue continued uninterruptedly under UN auspices. In the 1977 and 1979 High-Level Agreements, the principle of a bi-communal, bi-zonal federal solution was adopted. However, on 15 November 1983, the Turkish Cypriot side declared that, exercising its right to self-determination, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) had been established. Although this declaration of independence was not recognized internationally, Turkish Cypriots announced that they would continue to advocate a federation model in the negotiations. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, various UN plans (most notably the 1985–86 Draft Framework Agreement, the 1992 Ghali Set of Ideas, etc.) were presented to the sides, but each time they failed due to disagreements. Toward the end of the 1990s, the EU accession process of the Republic of Cyprus introduced a different dynamic into the search for a solution; it became apparent that despite the division of the island, the southern part of Cyprus could enter the EU on behalf of the whole island.

In the 2000s, hopes for a solution reached their peak. The comprehensive Annan Plan, prepared through the efforts of UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, was put to simultaneous referenda on both sides on 24 April 2004. Turkish Cypriots strongly backed the plan with a 64.9% (65%) “Yes” vote, while Greek Cypriots rejected it with 75.8% (76%) “No”. As reunification failed due to the Greek Cypriot rejection, the international community subsequently admitted the Republic of Cyprus (the Greek Cypriot government) as a full member of the European Union on 1 May 2004 on behalf of the entire island. This development reinforced among the Turkish Cypriot people—who had voted “yes” for a solution—the sentiment that the promises made to them had not been fulfilled; isolation and embargoes continued. The rejection of the plan consolidated the de facto division of the island and deepened the trust gap between the two sides.

In 2008, negotiations between the leaders Talat and Christofias restarted and achieved some convergences, but could not produce a comprehensive settlement. Most recently, the federal negotiations revived in 2015 by the leaders Akıncı and Anastasiades culminated at the Crans-Montana Conference in Switzerland in June 2017. With the participation of the guarantor states Turkey, Greece, and the United Kingdom, this conference was considered one of the closest moments to a solution. During the conference, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres presented a “package solution” proposal covering six chapters, including security and guarantees. However, the Greek Cypriot side adopted an uncompromising stance, insisting on “zero troops, zero guarantees from the first day,” particularly regarding Turkey’s military presence and the guarantee system, and even refused balanced proposals put forward by the UN. Despite the flexible and constructive approach of the Turkish Cypriot side, no agreement was reached on critical issues; in July 2017, Guterres announced that the conference had ended in failure. The Crans-Montana talks represented a turning point in the search for a federal solution, and the failure to reconvene a formal negotiation table afterwards brought new alternatives to the agenda.

After 2017, the Cyprus peace process entered a prolonged pause. In October 2020, with the election of Ersin Tatar as President of the TRNC, a new vision was put forward: the argument that the federation model had been exhausted, coupled with a formal proposal for a two-state solution on the basis of sovereign equality. Turkey likewise declared that it embraced this paradigm. Then-Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu stated that “we cannot embark on an open-ended adventure for a federation that will not yield results,” emphasizing that different solution options should be prioritized. At the informal 5+1 meeting held in Geneva in April 2021 under the UN framework, the Turkish side officially presented, for the first time, a detailed two-state vision and put forward as a precondition the recognition of the TRNC’s equal international status. However, the Greek Cypriot side and the international community rejected this thesis on the grounds that it contradicts UN resolutions. In 2022, Turkey reiterated its stance at the highest level by calling on the world to recognize the TRNC during the UN General Assembly. All these developments indicate that we have entered a period in which the negotiation parameters have fundamentally changed. At the same time, the partial opening of the long-closed Maraş (Varosha) area to civilian use by the TRNC in October 2020demonstrated that the status quo is now being challenged by different moves.

At this point, although the Cyprus issue remains unresolved, over 60+ years the sides have gone through numerous plans, countless meetings, and many mediators. Historically, the collapse of the 1960 partnership arrangement, the de facto partition in 1974, the rejection of the Annan Plan in 2004, and the failure of Crans-Montana in 2017 stand out as key turning points in reunification efforts. In light of these experiences, the question now on the agenda is whether the negotiation parameters will change. The quest for a solution to Cyprus’s future is being reshaped by lessons drawn from history.

Current Reunification Scenarios and Solution Models

Several scenarios have long been discussed for resolving the Cyprus issue. The most frequently mentioned models are as follows:

Bi-Communal Federation: The established solution model, defined by UN Security Council resolutions, foresees the establishment of a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation based on political equality on the island. Under this model, constituent states in the north and south would have their own autonomous administrations, while in external relations the united Cyprus state would be represented under a single sovereignty. The federation model has been presented in theory as the fairest balance, as it guarantees both the political equality of the two peoples and a certain degree of separate self-governance. Indeed, the UN and the international community have recognized a federation as the basis for a solution since 1977. However, in decades of federation negotiations, the sides could not reach agreement on critical issues (such as power sharing, rotating presidency, territorial arrangements, etc.); in particular, the Greek Cypriot desire for strong central government powers and the Turkish Cypriot sensitivity over political equality have made it difficult to implement this model. At this stage, although the federation officially remains on the table, its feasibility has become a matter of debate due to mutual mistrust.

Confederation: This model envisions two separate sovereign states forming a loose higher-level partnership through a framework agreement. In practice, it implies the presence of two independent states, but coordinated through certain joint organs. The confederation option was proposed notably by the Turkish Cypriot leadership in the 1990s under the formula of “cooperation between two sovereign states.” In this scenario, the existing TRNC and the Republic of Cyprus would recognize each other as separate states, and if this status were accepted internationally, a partnership would be established through inter-state agreements. Confederation has sometimes been brought up by the Turkish side as an alternative to the “exhausted federation”, but the Greek Cypriot side rejects it on the grounds that it would mean permanent partition. Furthermore, for a confederal solution to materialize, the TRNC would first need to be recognized or the Greek Cypriot side would need to accept a sharing of sovereignty; therefore, this scenario is seen as distant in practice.

Two Separate States (Partition): This scenario envisages the permanent consolidation of the division already in place, with two independent states on the island, one Turkish in the north and one Greek in the south. The Turkish Cypriot side and Turkey have increasingly emphasized that a solution is possible only on the basis of two sovereign states. Especially after the failure of federal initiatives in 2017, the “two-state solution” thesis has gained strength. Surveys also show that support for this option among Turkish Cypriots has increased: in a survey conducted in the TRNC in January 2020, 81.3% of Turkish Cypriots stated that they supported two separate states, while those favoring federation remained at 10%. From the Turkish side’s perspective, a two-state option is a realistic approach and a reflection of the existing de facto situation, as generations in the TRNC have lived within this order. However, in terms of international law and politics, it is the most challenging scenario. UN resolutions emphasize the principle of single sovereignty in Cyprus and do not recognize the structure in the north. The European Union has also stated at the highest level that it will “never accept a two-state solution”. For the Greek Cypriot side, too, dividing sovereignty is a red line. Therefore, the two-state formula, whose international recognition is seen as nearly impossible, would be less a negotiated solution and more a “de facto acceptance of the current situation”. Even if Turkey’s strong support and potential recognition moves by other countries were forthcoming, they might not suffice to alter the status quo; indeed, UN Security Council Resolutions 541 and 550 of 1983 declared the TRNC’s independence legally invalid. In sum, although the two-state option is present on the table as a view, its implementability in the international context is extremely low.

Apart from these scenarios, some authors propose hybrid formulas such as a “loose union under the EU umbrella” or a “decentralized federation.” For instance, the new Greek Cypriot leader Nikos Christodoulides has argued that a highly decentralized federation could address some of the Turkish side’s concerns. Ultimately, debates around the solution model focus on the question “which model is worth negotiating?”. Unless a common ground can be found between the sides, no scenario will be implementable. As of today, the Greek Cypriot side officially remains aligned with the federation line, while the Turkish side insists on the two-state thesis. For this reason, the core issue in Cyprus is to reach consensus on a shared vision.

The Role of International Actors

The Cyprus issue is a multi-faceted problem that concerns not only the parties on the island but also regional and global actors. In efforts toward reunification, the United Nations, the European Union, Turkey, Greece, the United Kingdom, and other relevant actors play prominent roles:

United Nations (UN): The UN, the primary mediator in the Cyprus issue, has deployed a peacekeeping force (UNFICYP) on the island since 1964 to help maintain security. Since 1968, the “Good Offices Mission” of the UN Secretary-General has hosted and facilitated negotiations. The UN’s solution parameters are based on a bi-communal, bi-zonal federation grounded in political equality. Within this framework, comprehensive plans (such as the 1992 Ghali Ideas, the 2004 Annan Plan, and the 2017 Guterres Framework) have been prepared, and successive Secretaries-General have tried to secure convergence between the sides. However, most recently, a diplomatic envoy appointed by Secretary-General Antonio Guterres to hold contacts on the island in 2023–24 reported that there is no common ground between the parties. The UN has had difficulty narrowing the deep gap between the parties regarding the vision for a solution. Nevertheless, Guterres has continued efforts to bring the sides together in informal formats as of 2025. The UN maintains its mediation while remaining committed to the parameters set by Security Council resolutions, and at the same time continues its mandate to preserve stability on the island.

European Union (EU): With the accession of the Republic of Cyprus to the EU in 2004, the Union became a significant dimension of the problem. While the southern part of Cyprus became an EU member, the application of the EU acquis in the northern TRNC was temporarily suspended. The EU has for years supported economic development in the north through mechanisms such as the Aid Programme and the Green Line Regulation, aiming at facilitating the integration of the Turkish Cypriot community into the acquis in the event of a solution. EU institutions have clearly expressed their stance in favor of a settlement in the form of a federation. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen emphasized that the EU would “never accept a two-state solution in Cyprus”, indicating that the Union remains firmly united on this issue. In 2023, through efforts by the Greek Cypriot leadership under Christodoulides, the EU signaled its intention to be more involved in the negotiations by appointing a special envoy to the process. In May 2025, the European Commission appointed former Commissioner Johannes Hahn as its Special Envoy for Cyprus, demonstrating its will to enhance its contribution to UN-led solution efforts. In its statement, the EU stressed that the Union remains committed to the goal of reunification of the island, based on UN Security Council resolutions and the EU’s principles and values, and that the solution must be compatible with and sustainable under EU law. In summary, the EU is a key actor in the resolution of the Cyprus issue both through its normative power (e.g., the status of a united Cyprus within the EU) and its incentives (financial aid, the broader dimension of Turkey–EU relations).

Turkey: For Turkey, the Cyprus issue is a “national cause.” As a guarantor of the constitutional order established in 1960 under the Treaty of Guarantee, Turkey intervened militarily in 1974, assuming a role as the protector of the Turkish Cypriots. Since then, through its military presence and financial and political support to the north of the island, Turkey has been a principal actor shaping the de facto situation. In the early 2000s, Turkey strongly supported the Annan Plan, thereby adopting a solution-oriented stance and even encouraging the Turkish Cypriot side to approve the plan. However, after the Greek Cypriot rejection of the referendum and especially after the failure at Crans-Montana in 2017, Ankara’s position underwent a transformation. Today, Turkey conditions any solution on the recognition of the sovereign equality of the TRNC and argues that the federation model has been exhausted. President Erdoğan, in speeches before the UN General Assembly in 2022 and 2023, called on the international community to recognize the TRNC, thereby putting the two-state vision on the global agenda. Turkey also considers its strategic interests in the Eastern Mediterranean (hydrocarbon exploration, maritime jurisdiction areas) as part of the Cyprus equation. On the security front, Turkey continues to regard the presence of Turkish troops on the island as vital for the security of the Turkish Cypriots and opposes the abolition of the 1960 guarantee system. Indeed, the guarantee issue was the most critical obstacle at Crans-Montana in 2017. Although Turkey’s vision for a solution in Cyprus lacks international acceptance, it remains decisive in terms of the de facto balance on the island. As the “motherland,” Turkey provides direct financial support to the TRNC economy and strengthens integration through energy and infrastructure projects. Ultimately, for any solution in Cyprus to be implementable, Turkey’s consent and active support are indispensable.

Greece: Due to historical, cultural, and political ties, Greece is the closest supporter of the Greek Cypriot side. As a guarantor of Cyprus’s independence under the 1960 arrangements, Greece became part of the tragedy in Cyprus through the Greek junta’s coup attempt in 1974. Following the restoration of democracy, Greek governments pulled the country toward a more international law-based stance on Cyprus. Officially, Greece declares that it supports the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic of Cyprus and that the solution in Cyprus should be a federation within the UN parameters. While Athens tries not to be a direct party at the negotiation table and leaves the leadership of the process to the Greek Cypriots, it has played active roles on security and guarantees in particular. For example, at the Crans-Montana Conference in 2017, the Greek foreign minister stated that the 1960 guarantee system was obsolete and should be abolished. While the Greek armed forces have not been officially present in Cyprus since 1974, “the protection of Hellenism in Cyprus” remains an important theme in Greek foreign policy. In recent years, Greece has sought to solidify Cyprus’s status through energy and defense cooperation frameworks in the Eastern Mediterranean with Egypt, Israel, and the Greek Cypriot administration. Greece’s positions within the EU and NATO also strengthen its hand vis-à-vis Turkey over the Cyprus issue. Overall, Athens wants a solution in which Turkish troops leave the island, the guarantee rights are abolished, and the Greek Cypriot side’s security concerns are addressed. In line with these goals, Greece acts in full alignment with the Greek Cypriot side in the Cyprus negotiations. It should also be remembered that any eventual settlement will require ratification by the Greek parliament; hence Greece is an integral actor in the solution equation.

United Kingdom: As the island’s former colonial ruler, the UK occupies a unique position in Cyprus. Under the 1960 Agreements, it retained sovereign base areas on 3% of the island’s territory, namely Akrotiri and Dhekelia. The UK, together with Turkey and Greece, is a guarantor state of Cyprus’s independence and constitutional order. Regarding a solution, the UK officially supports UN efforts and declares its commitment to the principle of a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation. London pursues a policy of balanced friendship towards both sides on the island, but due to its strategic interests in the Eastern Mediterranean (the continued presence of its military bases, regional stability, migration flows, etc.), it favors a manageable status quo. In the period of the Annan Plan in 2004, the UK even proposed to cede part of the land within its sovereign base areas to a united Cyprus as a contribution to a solution (a proposal that did not come into effect because the plan was rejected). In the latest negotiations, the UK participated in the talks as a guarantor but played a more background role. Although the UK has left the EU, it stresses that a solution in Cyprus would be in everyone’s interest. For the UK, reunification would offer economic and political opportunities, such as establishing special relations with a united EU-member Cyprus and expanding trade ties with the Turkish side. The UK also supports confidence-building measures between the two communities (for example, demining projects and cultural heritage preservation). In short, while the UK continues to voice support for a “fair and lasting settlement,” it will be attentive to ensuring that any agreement preserves its own military and geopolitical interests. Even if the guarantee system is abolished, the status of the British bases will remain a separate topic of negotiation on the table.

Other Actors: The Cyprus issue has attracted the interest of several major powers, especially the US and Russia. The United States has emphasized throughout the Cold War and beyond the importance of maintaining balances in Cyprus in favor of NATO. It actively supported the Annan Plan in 2004 and took initiatives to alleviate the isolation imposed on Turkish Cypriots after the referenda. Today, the US strengthens its relations with the Republic of Cyprus to counter Russian and Chinese influence in the Eastern Mediterranean; lifting the arms embargo on the south in 2022 is an indicator of this trend. Washington states that it would support any formula that both communities agree upon, yet in practice it backs the UN’s stance favoring federation. Russia, on the other hand, has traditionally been closer to the Greek Cypriot side and has opposed changes to the solution parameters in the UN Security Council. Moscow may be uncomfortable with the increased Western influence on the island and therefore tends to be cautious about radical moves on the Cyprus issue. Russian capital and citizens have long occupied a notable place in the economy of the south, which may incline Russia toward a continuation of the status quo. The permanent members of the UN Security Council (the US, Russia, the UK, France, and China) have for years adopted similar resolutions on Cyprus, emphasizing the island’s territorial integrity, the bi-communal federation principle, and the non-recognition of the TRNC. At the regional level, EU member states and neighboring Middle Eastern countries (such as Israel and Egypt) can also be considered indirect actors due to the impact of Cyprus’s stability on their interests. In summary, the reunification of Cyprus involves a multi-layered diplomatic chessboard, where the positions of international actors sometimes facilitate efforts for a solution and sometimes complicate them.

Social Tendencies and Reactions

In the Cyprus issue, the attitudes of political leaders are as important as the tendencies of the two peoples on the island regarding reunification. Over the years, the decades-long separation between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots has shaped public perceptions of one another in opposing ways. However, polls and field research show that both communities have not completely closed the door to a peaceful future:

Public Opinion Trends: The fact that the two communities voted in opposite directions in the 2004 Annan Plan referenda (Turkish Cypriots 65% “Yes,” Greek Cypriots 76% “No”) starkly exposed the trust gap between them. Yet there has been some rapprochement in the intervening years. Particularly since the opening of the crossing points in 2003, everyday interactions have increased, fostering curiosity and empathy among the communities. A comprehensive public opinion survey conducted in 2020 revealed that there is still a live desire for a federal solution on both sides: 66.5% of Greek Cypriot respondents and 63.6% of Turkish Cypriot respondents declared that they aspire to a united federal Cyprus. These significantly high percentages are important in showing that, at a time when official rhetoric has hardened, the peoples remain basically open to peace. The same study also found that the solution package proposed by Secretary-General Guterres in 2017, designed to balance the sensitivities of both sides (particularly on security guarantees and political equality), could be supported by 84% of Greek Cypriots and 60% of Turkish Cypriots. This suggests that a properly designed compromise could enjoy broad public acceptance.

Mistrust and Psychological Barriers: Of course, optimistic survey data do not mean that deep-rooted prejudices and fears have been fully overcome. Both communities still carry the legacy of past traumas. Among Greek Cypriots, there is widespread concern about the permanent presence of the Turkish military and the risk of becoming a minority in a reunited state. For many Greek Cypriots, the “1974 trauma” remains fresh and trust in the Turkish side is scarce. On the other hand, Turkish Cypriots have not forgotten the attacks between 1963 and 1974 and the Maronite–Greek blockades; they fear “if we share power again, will we experience the same things?” This historical spiral of mistrust has been reinforced by both the media and education systems. On both sides, school curricula long contained narratives that demonized the “other.” As a result, there are significant sectors that view the idea of reunification with suspicion. Looking specifically at younger generations, an interesting divergence emerges: a considerable portion of Turkish Cypriot youth communicate with their Greek peers via social media, whereas this rate is very low among Greek Cypriot youth. According to one study, 41% of Turkish youths reported interacting with Greek Cypriots on Facebook at least once a month, while this rate is just about 8% among Greek youths. This indicates that Turkish Cypriot society has become more open to contact and dialogue, whereas alienation appears stronger among the younger generation in the Greek Cypriot community. Population and welfare disparities also create psychological barriers: some circles in the south say they do not want to bear the economic burden of the poorer north if reunification occurs, while on the Turkish Cypriot side there are concerns that if reunification happens, their freedoms might be restricted.

Bi-Communal Contacts and Civil Society: Since the opening of the crossing points in 2003, there have been millions of crossings between the two sides over more than 20 years; people visited each other’s villages and towns, and established day-to-day interactions. These contacts have helped break down some prejudices. Academic studies demonstrate that increased face-to-face contact reduces fears about the other side and increases support for a settlement. In fact, the Bi-Communal Technical Committees, set up after 2008, implemented several small-scale confidence-building measures in areas such as health, culture, environment, and crisis management, achieving concrete successes like joint mine clearance and the restoration of cultural heritage sites. Moreover, civil society initiatives continue efforts to build public support for reunification. Peace activists from both sides organized joint actions on platforms such as “Unite Cyprus Now”; young people in 2011 set up a joint camp at the Ledra/Lokmacı crossing point under the name “Occupy Buffer Zone” to symbolically demonstrate their demand for a solution. Although such initiatives have not mobilized mass participation, they have resonated in the media and sent a grassroots message to political leaders. In the Turkish Cypriot community, there was particularly strong desire for a solution in the 2000s; their 65% “Yes” to the Annan Plan was a clear indication of this. Even though isolation did not end after the plan, Turkish Cypriots maintained their hope of integrating with the outside world. In recent years, this desire has somewhat diminished due to the growing political and economic influence of Turkey and the strengthening two-state discourse, yet a significant segment of the population continues to crave inclusion within international law. In the Greek Cypriot community, during the Annan Plan era, the “No” campaign argued that “a better solution is possible.” Over time, however, the Greek Cypriots have enjoyed the advantages of the status quo. The sense of prosperity and security brought by EU membership reduced the urgency of a solution. On the other hand, among the Greek Cypriot displaced population (those who lost their homes in 1974), frustration and longing have grown. Research indicates that many displaced Greek Cypriots, who once supported “no” in the belief that a better solution would come, now think that this was a mistake and are more open to compromise. Thus, over time, the view “we should have made peace while we had the chance” has become widespread among generations who lost their homes in 1974.

Intra-Community Political Divisions: There are disagreements about reunification within each community as well. On the Turkish Cypriot side, left-wing parties (such as CTP) advocate a federation and reunification within the EU, whereas the right-nationalist wing (UBP, HP, etc.) supports a two-state solution or, at the very least, deeper integration with Turkey. With the election of Ersin Tatar in 2020, the official policy of the TRNC shifted fully toward a two-state model, yet approximately half of the society still consists of people who favor a federation or some form of convergence—this can be inferred from the nearly split vote between the two candidates in the 2020 election. On the Greek Cypriot side, similarly, center-left parties (like AKEL) tend to favor a solution, while center-right (DISY) remains cautious and the far-right (ELAM) is openly anti-solution. Although Nikos Christodoulides, elected president in 2023, has introduced new ideas for a solution (such as a more active role for the EU), he essentially follows a nationalist line that leans toward a unitary-state perspective. Thus, within the Greek Cypriot community, one camp says “we must reunify under any circumstances,” while another insists “never, as long as the Turkish army is on the island.” These internal balances can restrict leaders’ room for maneuver. For instance, one of the factors limiting Anastasiades from showing more flexibility at Crans-Montana in 2017 was the likely backlash at home. Similarly, criticism that Akıncı “gave too many concessions” contributed to his failure to be re-elected in 2020.

In summary, the hearts and minds of the two peoples are crucial in the matter of Cyprus’s reunification. Although there is a substantial segment on both sides that keeps hope for peace alive, mutual mistrust remains a reality. At the societal level, improving perceptions of the “other” is essential for a possible agreement to pass referenda. Keeping channels of dialogue open between the two communities, and encouraging younger generations to get to know each other, are necessary. Civil society efforts and everyday interactions offer small but meaningful rays of hope when politics is deadlocked. Reunification can only happen when a significant majority of ordinary people on the island say “enough is enough, we want lasting peace.” Although that threshold has not yet been reached, public opinion trends show that the status quo is not seen as a permanent destiny.

Legal, Economic, and Security Dimensions

The establishment of a reunited Cyprus is not only a matter of political will; it also depends on solving numerous issues in legal, economic, and security domains. From property and territorial arrangements to citizenship statuses, from security guarantees to economic convergence, many structural issues require deep negotiation:

The Property Issue: One of the most intricate dimensions of the Cyprus problem is the matter of property rights over the homes, lands, and businesses left behind by tens of thousands of people who were displaced on both sides as a result of events between 1963 and 1974. When two homogeneous regions were created by the 1975 population exchange agreement, with 120,000 Greeks relocating to the south and 65,000 Turks to the north, abandoned properties came under the control of the new authorities. There have been longstanding claims over properties belonging to Greeks in the north and Turkish properties and villages in the south. Following individual property cases brought to the European Court of Human Rights (e.g., the Loizidou case), mechanisms such as the Immovable Property Commission in the north were established to provide compensation and limited restitution; yet these are only temporary measures. In comprehensive settlement negotiations, the property chapter has been among the toughest to resolve. The Annan Plan proposed complex formulas of compensation, restitution, and exchange; similarly, user rights and other mechanisms were discussed at Crans-Montana. Today, the property issue continues to trigger legal tensions. As some Greek Cypriot properties in the TRNC have been sold to third parties, Greek courts in the south have started issuing arrest warrants against foreign individuals involved in such transactions. In 2023–2024, several foreign businesspeople were arrested for this reason, prompting the TRNC authorities to adopt protective measures for their nationals who were involved in sales of Greek properties. This tension even affected the leaders’ meeting in May 2025; the Turkish side stressed that the Greek courts’ stance undermines the atmosphere of trust. In the event of reunification, resolving the property issue will require creative formulas that do not generate new victims. Most likely, this will involve establishing a compensation fund, balancing restitution and user rights based on certain criteria (for example, giving priority to the return of currently empty areas like Maraş/Varosha). As the property issue is directly linked to human stories, it is crucial for social peace after reunification.

Citizenship and Demography: Another sensitive dimension of the Cyprus problem is the demographic structure and citizenship on the island. After 1974, there was a substantial influx of population from Turkey to northern Cyprus. Today, a significant portion of the TRNC’s population has family roots in Turkey. The Greek Cypriot side regards this as an attempt to “alter the demographic structure through population transfer”, which it considers illegal. It also argues that the Turkish side has thereby strengthened its two-state objective. The Turkish side, however, integrated newcomers from Anatolia into the TRNC in the 1980s and 1990s, boosting its population. Today, the TRNC’s population is estimated at over 300,000 (including citizens and residents), while the Republic of Cyprus has around 900,000 inhabitants. In a solution, the question “which individuals will acquire citizenship of the new united Cyprus” becomes a major negotiation topic. The Annan Plan envisaged that a significant part of the Turkish settlers in the north (around 45,000 people) would receive citizenship of the united state, while the rest could remain under residence status. Similar debates are still relevant today: the Greek Cypriot side wants to limit the number of “settlers” and stop new inflows from Turkey, while the Turkish side emphasizes that people born and raised on the island for 50 years should not be considered foreigners. Hence, a formula of quotas or phased acceptance will likely be needed regarding citizenship. For instance, earlier considered criteria included caps such as “citizens of Turkey should not exceed 10% of the population in the north”. In addition, the status of tens of thousands of Turkish-origin residents in the TRNC who are not TRNC citizens must also be addressed in a settlement. This issue is not just about demography, but also about identity. Within the Turkish Cypriot community, the distinction between “native Cypriots” and “Turkish immigrants” is sometimes felt. In a united future, overcoming these distinctions is key for social cohesion. On the other hand, the statuses of Maronite, Latin, and Armenian minorities living in the south will also be redefined after reunification.

Security and Guarantees: Security is perhaps the most emotionally charged aspect of the settlement question in Cyprus. The 1960 system of guarantees (with Turkey, Greece, and the UK as guarantors) and the Treaty of Alliance allowed the stationing of limited Greek (950) and Turkish (650) troops on the island. However, after 1974, Turkey’s deployment of tens of thousands of soldiers on the island and a de facto balance with Greece created a security paradox. For Greek Cypriots, security means the withdrawal of Turkish troops and the end of unilateral intervention rights. The “zero troops, zero guarantees” formula has broad support in the Greek Cypriot community. For Turkish Cypriots, security means the continuation of Turkey’s guarantee to prevent a recurrence of past events. They respond, “without guarantees, without Turkey’s protection, we will have zero security”. This dilemma was a key obstacle to a settlement at Crans-Montana. The UN’s Guterres Framework proposed an innovative approach to security arrangements: it envisaged ending the guarantors’ unilateral intervention rights from day one and replacing them with an international implementation and monitoring mechanism alongside a phased withdrawal of Turkish troops. Moreover, a new “Security Agreement” involving multi-party guarantees acceptable to both communities was proposed. The Turkish side was, in principle, open to this concept, but the Greek Cypriot side would not sign without a clear timetable that would eventually remove Turkish troops altogether. In a post-settlement environment, security arrangements would likely include the following: an international peacekeeping force (under the UN or EU) stationed on the island for a transitional period; replacement of the current guarantee system with a new multi-party security agreement; and redefined roles for Turkey, Greece, and the UK (for example, consultation and involvement mechanisms without unilateral intervention rights). Another formula would be the inclusion of a revision clause in the agreement, allowing the parties to review security arrangements after a certain period (e.g., 10–15 years). The ultimate goal is to establish a balance in which both communities feel secure. A reunification in which one side feels threatened cannot succeed. Therefore, the issue of security guarantees must be negotiated very carefully with the participation of the guarantor states. In particular, the future of Turkey’s military presence on the island remains a vital concern for the Turkish Cypriot community.

Economic Convergence and Integration into the EU Acquis: The nearly 50-year separation between North and South Cyprus has also led to differences in their economic structures and levels of prosperity. South Cyprus is a small yet high-income economy (per capita GDP around 28,000 USD), using the euro; North Cyprus, meanwhile, is an economy closely integrated with Turkey, using the Turkish lira and with per capita income at roughly one-third of the south’s (approximately 10,000 USD). This disparity means that reunification will require a serious effort in economic convergence. In 2004, had the Annan Plan been accepted, the EU had prepared billions of euros in funds to support development in the north; similarly, in any future settlement, an EU Cohesion Fund would come into play. First, the transition from the Turkish lira to the euro in the north will have to be planned for financial and monetary stability. The unification of banking systems and the integration of fiscal and customs regimes will take time. From the public finance perspective, the southern part and the international community will likely need to contribute to bridging the north’s budget deficits. Another dimension is the funding of property compensation mechanisms—a large international financing pool will be required to compensate tens of thousands of properties. The EU has been providing annual financial assistance to the Turkish Cypriot community since 2006 and has taken steps to facilitate trade through the Green Line. Yet a comprehensive settlement would require the north’s full alignment with the EU acquis. Because the acquis communautaire is currently suspended in the north, a transitional period would be needed to bring TRNC institutions up to EU standards. This implies reforms in a wide range of fields, from the rule of law and food safety to environmental standards and competition rules. EU expert teams already carry out some technical harmonization work with TRNC authorities, for instance, to secure protected designation of origin (PDO) for halloumi/hellim cheese in the EU, inspections have been conducted in the north. In a reunified Cyprus, Turkish would become the EU’s 24th official language, and Turkish Cypriots would be represented in the European Parliament. Economically, reunification holds significant potential for synergy across the island: cooperation in tourism, education, trade, and energy could increase the prosperity of both sides. In particular, jointly exploiting the natural gas resources around the island could turn Cyprus into a regional energy hub. However, to realize these benefits, structural disparities must first be eliminated. Having functioned for decades under a subsidized model heavily dependent on Turkey, the northern economy will need time to stand on its own feet after reunification. Continuous international support (EU funds, World Bank loans, etc.) will therefore be critical in this process.

Governance and Constitutional Order: Establishing a reunited Cyprus also requires detailed arrangements regarding the constitutional structure and system of governance. For a partnership state based on the political equality of the two communities, the model envisaged in the Annan Plan included mechanisms such as rotating presidency, equal representation in the Senate, and community vetoes. Similar mechanisms will likely appear on the agenda again. For example, formulas such as separate majorities or cross-voting for key decisions of the federal government are likely to be discussed. The chapter on governance and power sharing must be designed by taking into account why the 1960 experience failed. The Turkish Cypriot side demands guarantees that in the new partnership they will “never again be excluded as in 1963.” The Greek Cypriot side, on the other hand, is concerned with the functionality of the state and may be hesitant about rigid power-sharing formulas. Striking this balance requires creative constitutional engineering. Most likely, a federal structure with two constituent states will be established, with a central government that has limited and clearly defined powers (such as foreign affairs, finance, and defense) and state-level administrations with broad autonomy. A bicameral federal parliament and mechanisms ensuring effective representation of both communities in the legislative process can be expected. Likewise, hybrid structures in the judiciary and mechanisms of cooperation for the police forces will need to be established. Another legal dimension concerns whether decisions and citizenships granted in the north until now will be recognized in the new order. For the continuity of international law, it is envisaged that, under the reunification agreement, existing arrangements in the TRNC would be gradually aligned with the federal legal framework while preserving acquired rights. This may include provisions recognizing the validity of current TRNC court decisions and land registries under certain conditions. Additionally, a Joint Commission or a High-Level Cooperation Council could be set up for the Transitional Period, which would manage critical issues in a coordinated manner until the unified state fully takes over.

As can be seen, the reunification of Cyprus requires a multi-dimensional and complex restructuring process. Each of the headings—property, citizenship, security, economy, and governance—must be elaborated in separate annexes and protocols of the agreement. Reaching consensus on these issues is not only a technical challenge but also a profoundly political process. The parties will try to find the middle ground through mutual concessions and creative formulas. Experts predict that any comprehensive settlement will be a large package, hundreds of pages long, with annexes and maps. While international experiences (such as German reunification or the Bosnian constitution) provide some precedents for Cyprus, the island’s unique problems require original solutions.

In conclusion: Solving the Cyprus issue and achieving reunification of the island depends on resolving not only historical mistrust but also current, concrete problems. It is necessary to craft a reunification model that meets the minimum expectations of both communities, has international legitimacy, and is economically sustainable. This is not easy—but it is not impossible either, provided that the parties do not lose sight of the bigger picture. The benefits of lasting peace (stability, prosperity, regional cooperation) are worth all these difficulties. The reunification of Cyprus could open a new chapter in the Eastern Mediterranean and consign to history a conflict that has lasted for generations. To reach this goal, beyond analytical thinking, patience, and dialogue, visionary leadership and societal readiness are also needed. As Cyprus stands once again at a historic crossroads, multi-dimensional assessments and determination are more essential than ever for a solution.