-

Multipolarity in Practice: Why a Fragmented World Is Not a Peaceful One

For much of the past decade, multipolarity has been presented as an implicit promise. As the dominance of a single power erodes, a more balanced, more just, and ultimately more peaceful international order is often assumed to follow. By 2024, however, the lived reality of multipolarity suggests a more sobering conclusion: fragmentation does not automatically produce stability.

The contemporary international system is no longer organized around a clear hierarchy. Power is distributed across multiple centers, each with its own interests, priorities, and narratives. In theory, this diffusion should reduce unilateral dominance and create space for dialogue. In practice, it has often produced ambiguity, rivalry, and a lack of shared responsibility.

What multipolarity has weakened most visibly is the idea of collective restraint. In a fragmented system, accountability becomes diluted. Crises are no longer addressed through coordinated frameworks, but through parallel, often competing initiatives. The absence of a common reference point makes it easier for actors to justify inaction, delay, or selective engagement.

From a peace-oriented perspective, this presents a serious challenge. Peace does not emerge simply because power is divided; it emerges when power is disciplined by norms, institutions, and political will. Multipolarity without cooperation risks becoming a landscape of unmanaged competition.

In 2024, this dynamic is visible across multiple regions. Conflicts persist not because solutions are unavailable, but because responsibility is diffused. Diplomacy becomes reactive, and peace initiatives struggle to gain traction.

Another overlooked consequence of multipolarity is narrative fragmentation. Competing interpretations of international law and legitimacy coexist without arbitration, weakening the normative foundations of peace.

This is not an argument for unipolar dominance. But neither should multipolarity be romanticized. Without coordination and shared responsibility, it becomes a permissive environment for prolonged instability.

Peace in a multipolar world requires intention, restraint, and renewed commitment to multilateral practice. Without these, peace does not collapse suddenly—it slowly fades.

-

Analysis of Turkmenistan–Russia Foreign Policy Relations

Introduction

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, relations between Turkmenistan and Russia have developed within the framework of a multidimensional strategic cooperation of significant importance. In 1995, Turkmenistan adopted a “permanent neutrality” status recognized by the United Nations and has since tried to maintain a balance among major powers. Russia, for its part, aims to preserve its influence in Central Asia and deepen cooperation with Turkmenistan in the fields of energy, economy, and security.

This report analyzes in detail the diplomatic relations, economic cooperation (especially in the energy sector), security cooperation, and major recent developments between the two countries. Each chapter discusses concrete developments, agreements, joint projects, and the broader international context. The report concludes with an overall assessment and forward-looking scenarios for the future of Turkmenistan–Russia relations.

Diplomatic Relations

Diplomatic relations between Turkmenistan and Russia have followed a fluctuating path since Turkmenistan gained independence in 1991. Under the first President Saparmurat Niyazov, Ashgabat pursued a largely isolated foreign policy based on “positive neutrality.” During this period, in an effort to limit Russian influence, Russian-language schools were closed, Russian was removed from the public sphere, and Turkmenistan downgraded its status in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) to “associate member.” Niyazov’s isolationist stance led to a cooling in relations with Moscow.

With the rise to power of Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow in 2007, contacts with Moscow were re-energized. In 2017, the two countries signed a “Strategic Partnership Agreement,” institutionalizing political dialogue. Within this framework, an economic cooperation program for 2017–2019 and about 80 joint projects were identified. In the same year, Turkmenistan appointed a permanent representative to the CIS Economic Council, and President Berdimuhamedow’s son, Serdar Berdimuhamedow, became co-chair of the Russian–Turkmen Intergovernmental Commission. Turkmenistan also began to participate as a guest in Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) summits and showed interest in Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) meetings as an observer. These steps show that, while maintaining its policy of multi-vector diplomacy, Ashgabat places importance on close dialogue with Moscow.

After Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow handed over the presidency to his son Serdar Berdimuhamedow in 2022, bilateral relations gained a new momentum. After assuming office in March 2022, President Serdar Berdimuhamedow paid his first official visit abroad to Moscow in June 2022, where the two sides signed the “Declaration on Deepening the Strategic Partnership between Turkmenistan and Russia.” This declaration set out future priorities in political, trade and investment, cultural and humanitarian, and security fields. During the same visit, a further 14 agreements were signed, and President Putin awarded Serdar Berdimuhamedow a Friendship Medal for his contribution to bilateral relations. These developments revealed that Turkmenistan’s new leadership also intends to maintain relations with Moscow at a strategic level.

The institutional dimension of diplomatic relations has also been strengthened. In June 2025, during Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s visit to Ashgabat, a 2025–2026 Cooperation Program was signed between the two foreign ministries. This program aims to regularize political consultations and maintain close coordination in multilateral platforms such as the UN, the Caspian Five, and the Central Asia+Russia format. Ashgabat and Moscow emphasize that they hold similar positions on regional and global issues. On sensitive issues such as the Ukraine crisis, Turkmenistan has been careful to maintain neutrality and avoid openly criticizing Russia, thereby seeking to keep the political basis of bilateral relations free of major friction.

Diplomatic relations are also reinforced in the cultural and humanitarian dimension. After declining in the post-Soviet period, Russian cultural influence has once again become visible in Turkmenistan in recent years. Currently, there are 71 schools in Turkmenistan where Russian is the language of instruction. Russia is also taking significant steps to win over Turkmen youth. For example, during his 2025 visit, Foreign Minister Lavrov proposed the establishment of a joint Russian–Turkmen university and the expansion of exchange programs for young diplomats and students. These initiatives reflect Moscow’s desire to preserve and expand its cultural influence in Turkmenistan. The Turkmen side has responded positively to such projects, aiming to strengthen ties of friendship with Russia at the societal level.

Despite these developments, Turkmenistan continues to pursue a policy of avoiding multilateral alliances that might restrict its sovereignty. Ashgabat is determined not to join Russia-centered integration projects such as the EAEU or the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). This stance is part of Turkmenistan’s strategy to preserve its independent foreign policy and principle of neutrality. For example, Ashgabat considers that EAEU membership would reduce its room for maneuver and instead explores more flexible forms of cooperation, such as observer status or limited sectoral partnerships. In sum, diplomatic relations are developing on the basis of mutual respect and strategic partnership, while Turkmenistan carefully protects its own foreign policy line.

Note: A table listing the major agreements signed between the two countries (with date, subject, and scope) could be prepared to visually present the milestones in diplomatic relations.

Economic Cooperation and the Energy Sector

Economic relations between Turkmenistan and Russia have been shaped predominantly around the energy sector and have witnessed notable developments in recent years. Turkmenistan, which possesses the world’s fourth-largest natural gas reserves, is a key actor in energy exports. For many years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Turkmen gas reached world markets primarily via Russia; this made Gazprom–Turkmengaz cooperation the backbone of bilateral relations.

However, tensions emerged between the parties in the 2000s. In April 2009, an explosion on the Central Asia–Center pipeline, which carried natural gas from Turkmenistan to Russia, led to mutual accusations and brought planned new pipeline projects to a halt. After this event, economic and political contacts were reduced to a minimum. In 2016, Gazprom completely stopped importing gas from Turkmenistan and took Turkmenistan to international arbitration due to a pricing dispute. This period represented the low point in bilateral relations. While China emerged as Turkmenistan’s sole buyer of natural gas, even large-volume sales to Beijing failed to generate the desired revenue because loans were being repaid with gas deliveries.

The year 2019 marked the beginning of renewed rapprochement in energy cooperation. Gazprom withdrew its legal claims against Turkmenistan and signed a five-year gas purchase agreement, under which it resumed imports of Turkmen gas in 2019 at a volume of 5.5 billion cubic meters per year. Although the volumes were far below previous levels and prices were less favorable for Turkmenistan, the agreement provided Ashgabat with a critical cash flow and somewhat strengthened its hand vis-à-vis China. With Gazprom’s resumption of gas purchases, Turkmenistan obtained some relief from its economic crisis and gained leverage against Beijing, which had been its sole buyer.

Another dimension of recent energy cooperation has been the discussion of new pipeline routes and corridors. Turkmenistan has long sought to diversify its energy export routes and has promoted several initiatives. The Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India (TAPI) gas pipeline project is one of the most prominent. The Taliban’s seizure of power in Afghanistan in 2021 raised uncertainty about the project’s future, but Ashgabat has tried to advance TAPI by maintaining cordial relations with the Taliban.

At the same time, the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline, which would transport Turkmen gas to Turkey and Europe via Azerbaijan across the Caspian Sea, has remained on the international energy agenda. In 2021, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan resolved their long-standing dispute over the Dostluk (Friendship) hydrocarbon field and agreed to jointly develop it. Russia’s Lukoil announced its willingness to become the operator of this project. Moscow welcomed this development because Russian involvement in regional energy projects helps it maintain its geopolitical influence. Nevertheless, Russia has generally been reluctant toward the idea of Caspian routes for gas exports to Europe. The 2018 Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea requires the consent of littoral states for sub-sea pipelines; invoking environmental concerns, Moscow has sought to keep tight control over Turkmenistan’s access to Western markets.

In recent years, non-energy economic cooperation has also expanded significantly. Notably, there have been sharp increases in trade volume since 2020. Despite the global slowdown caused by the pandemic, non-gas trade between the two countries rose by 40% in 2020, reaching 970 million USD. In 2021, total trade amounted to around 865 million USD, while in 2022 bilateral trade volumes jumped to about 1.6 billion USD. Growth continued in 2023, and for 2024 the trade volume is estimated to be close to 1.8 billion USD. In the first months of 2025, trade posted an additional increase of about 58% compared to the same period of the previous year, indicating an exceptional surge. These figures show that economic ties between Turkmenistan and Russia are strengthening and diversifying beyond the energy sector. As of 2022, Russia had become one of Turkmenistan’s top three trading partners.

Note: A line chart showing the trajectory of Turkmenistan–Russia trade volumes from 2017 to 2025 would be useful to visualize the evolution of economic cooperation over time.

In terms of trade structure, Turkmenistan imports capital goods, machinery and equipment, metal products, foodstuffs, and consumer goods from Russia, while Russia imports from Turkmenistan some natural gas (during 2019–2023 under the agreed volumes), as well as petroleum products, chemicals, and textile products. Due to the limited range of Turkmen exports, the trade balance tends to favor Russia, with Turkmenistan incurring a trade deficit vis-à-vis its northern neighbor. This reveals that Turkmenistan’s economy still relies heavily on hydrocarbon revenues and has not sufficiently diversified.

A further dimension of economic cooperation lies in the relations between Turkmenistan and Russian regional actors. In particular, the Republic of Tatarstan maintains close economic ties with Turkmenistan. Tatarstan’s oil company Tatneft has been active in Turkmenistan’s oil fields since 2008, and in 2020 it signed a service agreement with the state-owned Turkmennebit to improve the productivity of oil wells until 2028. Similarly, Tatarstan-based KAMAZ delivered about 2,000 vehicles to Turkmenistan between 2019 and 2021 and is expanding its maintenance and service network in the country. The Kazan Helicopter Plant has supplied air ambulances for Turkmen medical aviation, while Ak Bars Shipyard has played a role in modernizing Turkmenistan’s fleet, delivering a passenger vessel and constructing additional ships. Such comprehensive sub-national cooperation is part of Moscow’s strategy to strengthen ties with Turkmenistan at multiple levels. Regions such as Tatarstan, with their cultural affinity (Turkic language, Islam) and industrial strength, help Russia balance Chinese and Western influence in Turkmenistan.

Beyond energy, investments and projects in other sectors are also noteworthy. Leveraging its geographic location, Turkmenistan seeks to become a key node in regional transport corridors. Together with Russia, Turkmenistan is working on the North–South Transport Corridor, which connects Russia to the Indian Ocean via Iran. In this context, effective use of Turkmenistan’s Turkmenbashi port on the Caspian Sea and capacity increases on the Russia–Kazakhstan–Turkmenistan–Iran railway lines are on the agenda. During Lavrov’s 2025 visit, attention was drawn to Turkmenistan’s position at the intersection of East–West and North–South corridors, and its potential role in the Middle Corridor linking China, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Europe. These projects are in line with Turkmenistan’s ambition to become a logistics hub in international trade, and by supporting these efforts, Russia both derives economic benefits and helps preserve its regional influence.

In summary, today’s economic cooperation rests on two main pillars:

- Partnerships in the energy sector

- Trade and investment projects beyond energy

In energy, Russia acts both as a buyer and a transit country for Turkmen gas, but the rising share of China in recent years and Turkmenistan’s search for alternative markets complicate the picture. Notably, in 2024 Russia overtook Turkmenistan as China’s largest gas supplier. This development, linked to Moscow redirecting its gas toward China, exposes Turkmenistan to increased competition in the Chinese market.

For its part, Turkmenistan has experimented with swap deals via Iran to send gas to Turkey and Azerbaijan and, indirectly, to Europe. In March 2023, a tripartite swap mechanism was launched, whereby Turkmen gas was transported via Iran to Turkey and from there to Europe for the first time. This new route attracted international attention and shows that Turkmenistan is exploring options beyond Russia and China, pursuing a multi-vector strategy in energy exports.

Security Cooperation

Security and military cooperation constitute the most cautious and limited dimension of Turkmenistan–Russia relations. Under its permanent neutrality doctrine, Turkmenistan has pursued an inward-looking, alliance-free security policy since independence. As a result, it is the Central Asian country that has the least extensive security partnership with Russia. Ashgabat has systematically rejected participation in Russia-centered security platforms such as the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and has generally refrained from participating even as an observer in joint military exercises. For instance, while Uzbekistan — despite not being a CSTO member — occasionally participates in military drills with Russia, Turkmenistan prefers to stay apart from such activities. This shows Turkmenistan’s desire to retain unilateral decision-making autonomy in security matters while accepting the risks of relying predominantly on its own capabilities.

Historically, Turkmenistan had a form of security guarantee arrangement with Russia in the early years of independence. Under an agreement signed in July 1992, Russia undertook to act as a guarantor of Turkmenistan’s security, allowing Ashgabat to postpone the immediate need to build its own armed forces. During the 1990s, some segments of Turkmenistan’s borders were guarded by Russian border troops under this arrangement. From the 2000s onwards, however, Turkmenistan focused on strengthening its own armed forces, especially to protect its interests in the Caspian Sea. After 2010, Ashgabat began building a navy as part of this effort. The naval base inaugurated in 2021 at Garshi (Turkmenbashi) and the acquisition of new vessels were important steps in enhancing Turkmenistan’s defense capabilities. In this military modernization process, Russia did not act as Turkmenistan’s primary supplier of major weapon systems. Instead, Ashgabat procured defense equipment from a range of sources (Turkey, China, Western countries). According to expert assessments, Turkmenistan has significantly reduced its dependence on Russian weaponry and diversified its arsenal.

By the late 2010s, regional security dynamics compelled Turkmenistan to take some selective cooperation steps. In particular, there was intensified dialogue between Moscow and Ashgabat regarding threats emanating from Afghanistan. With the revival of bilateral relations after 2017, Russia encouraged Turkmenistan to take more concrete steps in security cooperation. These efforts culminated in the signing of a “Joint Security Cooperation Agreement” in October 2020. This was significant as it represented the first comprehensive agreement in the security field in 17 years (the previous similar agreement dated back to 2003). The timing of the agreement is noteworthy; many observers argue that Russia used its economic leverage to persuade Turkmenistan to sign. While Turkmenistan continues to publicly assert that its borders are secure, independent sources report incidents of clashes and incursions along the Afghan border. In 2020, reports emerged claiming that Russian troops had covertly supported Turkmen units along the Afghan frontier, but Ashgabat officially denied these claims on the grounds that they contradicted its foreign policy principles.

Turkmenistan and Russia share a common interest in stabilizing Afghanistan. Both countries have expressed support for a diplomatic, inclusive political settlement in Afghanistan following the rise of the Taliban. Before the fall of Kabul, they maintained contacts with both the Afghan government and the Taliban, seeing the latter as a necessary part of the solution. After the Taliban’s takeover in 2021, Turkmenistan and Russia continued to coordinate on humanitarian aid and infrastructure projects. For its own economic benefit, Turkmenistan has placed particular emphasis on maintaining good relations with the Taliban to advance the TAPI project and has consulted Moscow on these matters.

However, there are subtle differences in the strategic objectives of the two countries in Afghanistan. Russia has seen the post-Taliban security vacuum as an opportunity to enhance its influence in Central Asia and to consolidate the regional security architecture under its leadership. Turkmenistan, on the other hand, has focused on being affected as little as possible by these developments while preserving its neutral identity. While Moscow would like to pull Turkmenistan more firmly into its security orbit (for example by encouraging CSTO observer status or participation in joint exercises), Ashgabat prefers informal and bilateral cooperation and continues to avoid formal alliances. At this point, China also enters the equation: in recent years, China has become more visible in the security sphere in Central Asia by providing equipment and even establishing facilities. When Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Ashgabat as his first stop on a Central Asia tour in July 2021 and offered Chinese support for Turkmenistan’s border security, this was particularly significant. Turkmenistan welcomed this proposal and took steps to allow Chinese private security companies to protect Chinese investments on its territory. Ashgabat thus seeks to strengthen its hand by obtaining support from another major power like China before deepening security cooperation with Russia, thereby avoiding excessive dependence on Moscow and pursuing a fine balance between the two.

In the context of regional security, the status and security of the Caspian Sea are also important issues. In August 2018, the five littoral states (including Turkmenistan and Russia) signed the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea, ending years of uncertainty. The convention primarily addresses the division of the seabed and the principle of preventing military presence by external powers. In October 2024, Russia, Iran, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan signed a Comprehensive Strategic Cooperation Agreement on naval cooperation in the Caspian, emphasizing the rejection of foreign intervention in the region.

Notably, Turkmenistan did not participate in this meeting. Ashgabat likely preferred to stay out of this multilateral maritime security initiative because it saw it as incompatible with its neutrality or not fully aligned with its own interests. Russia, which has the strongest navy in the Caspian, opposes permanent deployments by outside actors such as the US and NATO, and views the Caspian as an area where only littoral states should be influential. Turkmenistan, however, adopts a more cautious and reserved approach and may be reluctant to fully endorse a vision of the Caspian controlled solely by the littoral states under Russia’s leadership. This example is consistent with Turkmenistan’s reflex of staying away from binding multilateral security arrangements.

In conclusion, Turkmenistan–Russia security cooperation is a controlled and limited partnership. While Moscow would like to integrate Ashgabat more deeply into its security architecture, Turkmenistan prefers to maintain cooperation in less visible forms such as shadow support or bilateral intelligence sharing. Security dialogue is not absent: intelligence is exchanged on such issues as terrorism, border security, and drug trafficking, and Turkmen officers occasionally receive training in Russian military institutions. Nevertheless, Turkmenistan neither joins Russian-led alliances nor participates in joint military operations. This carefully calibrated distance allows Turkmenistan to address its security concerns while preserving its image of neutrality.

Key Recent Developments (Post-2020)

In the period after 2020, Turkmenistan–Russia relations have seen significant developments in the diplomatic, economic, and security dimensions. The main developments can be summarized chronologically as follows:

2020

- A historic step was taken in the security dimension, which had long remained underdeveloped, when Turkmenistan and Russia signed a Joint Security Cooperation Agreement. This was the first comprehensive agreement in the security field since 2003.

- Allegations surfaced that Russian troops were secretly supporting Turkmen forces on the Afghan border, but Ashgabat officially denied these claims, stating they were incompatible with its foreign policy principles.

- Despite the pandemic, bilateral trade increased by 40% and reached a record level, indicating a trend toward diversification in economic relations.

2021

- To deepen economic cooperation, Turkmenistan approved the 2021–2023 Russia–Turkmenistan Economic Cooperation Program. This program envisaged new joint projects in many sectors including industry, agriculture, finance, and energy.

- Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan reached an agreement to jointly develop the Dostluk oil and gas field, marking an important step toward diversifying Turkmenistan’s energy exports. Russia welcomed the agreement and Lukoil declared its readiness to participate in the project.

- The visit of the Chinese foreign minister to Ashgabat was seen as a move by Turkmenistan to draw closer to China in the energy and security spheres, a development that Moscow has taken into account in shaping its Turkmenistan policy.

2022

- In March 2022, Serdar Berdimuhamedow became president, marking a leadership change in Turkmenistan. His first official foreign visit was to Moscow in June 2022, where the parties signed the Declaration on Deepening the Strategic Partnership between Turkmenistan and Russia.

- Fourteen new agreements were signed during the visit, expanding cooperation in trade, investment, culture, and security.

- Ashgabat hosted the 6th Caspian Summit, which Russian President Putin attended. The summit focused on the legal status of the Caspian Sea and cooperation there.

- Turkmenistan participated in the first summit of the Central Asia+Russia format, indicating a more active role in multilateral regional diplomacy.

2023

- Trade continued to grow, and by the end of the year, bilateral trade volumes were expected to reach the 1.7–1.8 billion USD range.

- The Russian ambassador in Ashgabat underlined the strength of cultural relations, noting that 71 schools with Russian as the language of instruction were operating in Turkmenistan, marking a renewed spread of the Russian language.

- President Serdar Berdimuhamedow and President Vladimir Putin held a phone conversation to discuss bilateral ties and cooperation, and later Berdimuhamedow attended the informal CIS leaders’ summit in St. Petersburg.

- Turkmenistan gave signs of a modest opening toward the West. In March 2023, for the first time, Turkmen gas reached Europe via Iran and Turkey under a swap arrangement, at a time when US and EU interest in Turkmenistan was rising due to energy security concerns.

2024

- At the beginning of the year, the five-year gas purchase agreement signed between Gazprom and Turkmenistan in 2019 expired and was not renewed. Accordingly, Gazprom stopped planned gas purchases from Turkmenistan from 2024 onward.

- By significantly boosting gas exports to China, Russia surpassed Turkmenistan and became China’s largest gas supplier, forcing Ashgabat to rethink its export strategy.

- Turkmenistan signed an agreement with Uzbekistan to set up a joint free trade zone in the border region, taking a step toward regional economic integration.

- Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Iran signed a document on enhanced security cooperation in the Caspian Sea, but Turkmenistan did not participate, highlighting Ashgabat’s distance from multilateral security understandings.

- Turkmenistan began negotiating a new version of the economic cooperation program with Russia to cover the period after 2024, likely specifying a fresh list of joint projects for 2025–2027.

2025

- In June 2025, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov paid an official visit to Ashgabat. During his talks with President Serdar Berdimuhamedow and Foreign Minister Rashid Meredov, they discussed the acceleration of economic and humanitarian projects, the follow-up of joint projects under the intergovernmental commission, and regional security issues.

- As a result of the visit, the two foreign ministries signed the 2025–2026 Cooperation Program, stressing close coordination within the CIS, the Caspian Five, the Central Asia+Russia format, and the UN.

- Lavrov publicly announced the plan to establish a Russian–Turkmen university in Ashgabat and to expand youth exchanges, a concrete manifestation of Russia’s effort to broaden its cultural influence.

- The United States’ growing diplomatic interest in Turkmenistan drew attention. US officials held contacts with Turkmen counterparts, praising Turkmenistan for facilitating certain evacuation and transit operations during regional crises and expressing the desire to enhance commercial ties.

- Russian media speculated that a new long-runway airport opened in the town of Jebel in western Turkmenistan might be used by US military transport planes, causing unease in Moscow. These developments show that, as of 2025, Turkmenistan has become the object of an intensifying competition for influence between Russia and the West.

Overall Assessment and Future Prospects

Although Turkmenistan–Russia relations have advanced in recent years to the point where they are labeled a strategic partnership, this rapprochement has not produced a fundamental shift in Turkmenistan’s foreign policy orientation. Ashgabat continues to place its neutrality and balancing strategy at the center of its diplomacy. Despite growing economic and political cooperation with Russia, Turkmenistan remains determined not to join Russian-led multilateral structures such as the EAEU, CSTO, or SCO. Thus, intense bilateral contacts coexist with a cautious stance toward deeper multilateral integration. This reflects Turkmenistan’s overarching strategy of keeping equal distance from major powers (Russia, China, and the United States).

From a perspective of current interests, Moscow and Ashgabat’s priorities converge in many areas. The two countries share similar concerns and goals regarding Afghanistan’s stability and the fight against regional terrorism and drug trafficking. In the economic realm, Turkmenistan wants to reduce its energy dependence on both China and Russia, which drives it toward projects like TAPI and the Trans-Caspian pipeline. Yet, given existing constraints, it is unlikely that these projects will be fully realized in the short term. Consequently, Turkmenistan will continue, at least for the near future, to rely primarily on China in terms of gas exports and on Russia in security matters. This dual dependence forces Ashgabat to pursue a careful balancing policy.

Looking ahead, both domestic and external dynamics will shape the trajectory of Turkmenistan–Russia relations. Domestically, Turkmenistan faces significant economic challenges and social pressures: high inflation, unemployment, and emigration are all pressing problems. These conditions may push Ashgabat to seek more external resources and investments. If Turkmenistan’s economic distress deepens, it may opt for closer economic cooperation with Russia, possibly including requests for Russian loans or investments. Indeed, assessments that Turkmenistan has drawn closer to Russia in recent years are often linked to its internal economic needs. On the other hand, if China offers increased gas purchases and greater financial support, Ashgabat is likely to continue prioritizing its relationship with Beijing. This points to a competitive and balancing game between Russia and China over influence in Turkmenistan.

In the international arena, Russia’s war in Ukraine and the subsequent sanctions have pushed Moscow to seek deeper engagement in Central Asia. For Russia, Turkmenistan has become a front in a broader geopolitical contest. The growing interest of the United States and Europe in Central Asia (new EU–Central Asia formats, US diplomatic initiatives in the region) will also affect Turkmenistan. Ashgabat will try to cautiously develop its relations with the West while avoiding a loss of trust in Moscow. For example, Turkmen gas is viewed as an important option in EU efforts to diversify energy supplies. If concrete finance and security guarantees can be offered for the Trans-Caspian pipeline, Turkmenistan may move forward on this project. In such a scenario, Russia might seek to block it on environmental or political grounds. Thus, Turkmenistan’s future energy export moves could become potential points of tension in its relations with Russia.

In the field of security, the vacuum created after the withdrawal of US/NATO forces from Afghanistan persists. While Russia aims to consolidate its role as security provider in Central Asia, Turkmenistan is inclined to cooperate de facto without formally recognizing this role. In the event of increased instability emanating from Afghanistan (such as border violations or refugee flows), Turkmenistan may be compelled to seek greater technical support from Russia. The 2020 agreement provides a framework for such cooperation, but Turkmenistan is likely to continue to act with great discretion to protect its neutral image. At the same time, if China’s security presence in the region expands (for example through bases or joint patrols in neighboring countries), this could offer Turkmenistan an alternative security anchor and encourage Ashgabat to balance Beijing and Moscow in security as well.

Overall, the future of Turkmenistan–Russia relations is likely to be characterized by gradual and cautious progress. Economically, trade and investments will probably continue to grow, and the two sides will seek new cooperation opportunities in non-energy sectors such as agriculture, textiles, and transport. Diplomatically, Turkmenistan will maintain a posture similar to that of the Non-Aligned Movement, avoiding actions that might antagonize any major power. This implies a close but carefully managed partnership with Russia. Moscow, accepting Ashgabat’s stance, will rely more on soft power instruments (education, language, culture) and economic incentives to preserve and expand its influence. The planned joint university in Ashgabat and cultural centers are part of this strategy.

It is not expected that Turkmenistan will become a full member of the EAEU or CSTO in the foreseeable future; however, it may keep the door open to partial involvement through observer status or special partnership agreements. Similarly, while Turkmenistan is interested in multinational energy projects, their implementation may be delayed by regional instability (Afghanistan) and great power rivalries (Russia–EU–China). In this case, Ashgabat will aim to optimize existing export routes via China and, to a limited extent, Russia.

In conclusion, Turkmenistan–Russia foreign policy relations are rooted in deep historical, cultural, and geographical ties and have advanced significantly in recent years. At the same time, Turkmenistan has clearly delineated the limits of this relationship within the framework of its neutrality. While the two countries continue to cooperate closely on the basis of pragmatic interests, Turkmenistan skillfully applies a policy of balance to maximize its national interests. The future trajectory of relations will be determined largely by developments in energy markets, the geopolitical climate in Central Asia, and Turkmenistan’s domestic economic situation. As long as Ashgabat manages to preserve its delicate balance among major powers, Turkmenistan–Russia relations are likely to remain based on a win–win formula, benefiting both countries and contributing to regional stability.

-

The Threats of Religious Extremism and Terrorist Organizations in Central Asia

As seen on the map, the Central Asian region consists of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, and borders Afghanistan to the south. In the post-Soviet period, the expansion of religious freedoms has fueled radical tendencies among certain segments of society. For instance, between 2010 and 2016, Kyrgyz security authorities reported that 863 of their citizens had participated as foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq.

Within this framework, foreign fighters originating from Central Asia joined the Iraq–Syria jihad in the thousands, posing a potential threat to the region. Indeed, between 2012 and 2018, more than 4,000 individuals participated in armed conflicts, making Central Asia the third-largest source of jihadist fighters. By 2015, approximately 1,400 of these fighters (around 500 of whom were Uzbek nationals) were actively fighting in Syria and Iraq; in subsequent years, the total number of Central Asian foreign fighters reached between 5,000 and 6,000.

As a result of these conflicts, Uzbek-origin militant groups such as Katibat Imam Bukhari (KIB) and Katibat al-Tawhid wal Jihad assumed significant roles, while northern Afghanistan and border regions of Central Asia provided these groups with operational bases.

Although Central Asian countries have not experienced large-scale terrorist attacks to date, they remain concerned about threats originating outside the region. An Israel-based analysis noted that major attack attempts targeting Central Asia in 2023 originated not from Afghanistan, but from Russia and Iran, emphasizing that militants under the Islamic State Khorasan (ISK) umbrella were planning operations in both countries.

In reality, in 2022, militants in the Kandahar region launched rocket attacks just beyond the Afghan border, targeting the Uzbek border city of Termez and areas of Tajikistan. Following these attacks, ISK released a statement in Uzbek declaring a “major jihad against Central Asia.”

Meanwhile, the number of militants of Tajik origin has increased rapidly; most of those killed in the March 2024 attack in Moscow were Tajik nationals. International observers have emphasized that these attacks signal a shift in ISK’s strategy, highlighting the rapid recruitment of Central Asian—particularly Tajik—militants and the planning of new operations.

Participation of Regional Citizens

Many young individuals of Kyrgyz, Kazakh, and Uzbek origin have been linked to radical organizations. For example, a United Nations report indicated that at least 863 individuals from Kyrgyzstan had participated as fighters in conflict zones by 2016. Similarly, hundreds of individuals from Kazakhstan and other Central Asian states joined jihadist groups centered in Damascus and Baghdad.

In particular, Uzbek-origin groups such as KIB and KTJ have played active roles in Syria for years, maintaining ties with al-Qaeda and gaining substantial battlefield experience. During this period, Tajik and Uzbek militants from northern Afghanistan and surrounding areas also rose within ISK ranks, playing significant roles in attacks in Iran and Russia.

Consequently, the return of large numbers of Central Asian fighters poses a serious risk, as they may transfer their combat experience into domestic violence within the region.

Organizational Structures of Terrorist Groups and the Risk of Expansion

Both ISIS-affiliated and al-Qaeda-linked groups are striving to expand their influence in Central Asia. ISK, the Afghan branch of ISIS, has recruited heavily from Kyrgyz, Kazakh, Uzbek, Tajik, and Uyghur minorities, forming alliances with anti-regime militants.

At the same time, transnational organizations such as Hizb ut-Tahrir and pro-Taliban local actors continue to pose destabilizing risks. In recent years, some Central Asian suspects arrested in Türkiye, Europe, and the Middle East were identified as members of ISIS- or al-Qaeda-linked cells.

For instance, in 2024, a cell dismantled in Istanbul was reported to be led by a Tajik national, with members consisting of a Tajik-Uzbek duo. This demonstrates that individuals radicalized through education or labor migration may engage in both external attacks and domestic organizational activities upon returning to the region.

Regional Measures and Warnings

States such as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan are increasingly aware of this threat. In November 2023, a member of the Kazakh parliament warned about the spread of movements “outside traditional Islam.” Similarly, the head of Kyrgyz intelligence acknowledged the infiltration of “foreign ideologies” into the country.

At a meeting held near Samarkand, Uzbek Prime Minister Aripov and security officials emphasized that a new wave of religious radicalization represents a “persistent and burning issue.” Security forces have intensified preventive operations; in 2024, Kazakhstan’s National Security Committee detained 23 individuals during raids on 49 radical cells and prevented two planned attacks.

During the same period, Kyrgyz authorities reported dismantling 15 ISIS-linked cells. Similar operations have continued in Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. While these measures are significant, experts warn that authoritarian repression may fuel radicalization, emphasizing the need to balance security operations with civil society engagement.

Warnings and Future Assessment

In light of these developments, several critical warnings can be issued to Central Asian governments:

Attention to Cross-Border Threats: Groups such as ISK are no longer limited to Afghanistan and are now targeting Russia, Iran, and Europe. For example, the March 2024 Moscow attack, which killed 133 people, was claimed by ISIS-Khorasan, with the perpetrators identified as Tajik nationals.

Returning Foreign Fighters: Thousands of Central Asians previously fought within ISIS ranks. Those detained in camps or deported may destabilize domestic security upon return, necessitating enhanced screening and reintegration programs.

Preventing Radicalization and Protecting Human Rights: While strict security measures are essential, restricting political freedoms may intensify radicalization. Governments should pursue fair policies and social inclusion, strengthening education systems that promote tolerance and youth employment to counter extremist propaganda.

International Cooperation: Strengthening intelligence sharing and border controls among Central Asian states is crucial. Counterterrorism exercises and legal cooperation should be enhanced through mechanisms such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the United Nations. Expanding cooperation with external partners, including the United States, Europe, and China, can help disrupt ISIS-linked financing and arms flows.

Conclusion

As of 2024, the threat of extremist jihad in Central Asia has not yet translated into widespread domestic attacks; however, the expansion potential of external organizations remains high. In particular, Central Asian fighters with experience from the Syria-Iraq war and the presence of ISIS-K in Afghanistan pose long-term threats to societal security.

Regional states must remain vigilant, preventing radicalization through social policies while maintaining firm security measures. This analysis aims to warn Central Asian governments against this evolving threat.

-

The United Nations in 2024: Crisis Management Without Peacebuilding

In 2024, the United Nations remains at the center of almost every major international crisis—yet rarely at the center of their resolution. From armed conflicts to humanitarian emergencies, the organization is present, vocal, and active. What is increasingly absent, however, is a sense that these engagements are translating into durable peace.

The UN’s approach in recent years has leaned heavily toward crisis management. Statements are issued, emergency sessions convened, and humanitarian corridors discussed. These actions matter, but they often function as containment rather than transformation. The underlying political conditions that generate conflict are addressed cautiously, if at all, constrained by institutional limits and power dynamics within the system.

This pattern is not new, but in 2024 it has become more visible. The Security Council remains paralyzed by veto politics, turning peace into a negotiable outcome rather than a collective obligation. Preventive diplomacy—long emphasized in UN doctrine—continues to receive rhetorical support while remaining operationally underpowered. As a result, the organization reacts to crises it once claimed it could help prevent.

From a peace-oriented perspective, this gap between mandate and impact is deeply troubling. Peacebuilding is not a luxury that follows stability; it is a prerequisite for it. Yet peacebuilding efforts are frequently sidelined in favor of short-term stabilization measures that address symptoms without confronting causes.

Another challenge lies in credibility. When the UN speaks forcefully in some crises and cautiously in others, perceptions of selectivity intensify. This inconsistency undermines trust in the UN as a neutral guardian of international peace.

None of this suggests that the United Nations is irrelevant. The absence of any alternative global platform with comparable legitimacy makes the UN indispensable. But indispensability should not shield the institution from critique.

In 2024, the UN’s central challenge is not capacity, but courage—courage to prioritize prevention over reaction, and peacebuilding over containment.

If the United Nations is to remain a meaningful pillar of global peace, it must move beyond managing instability and reclaim its role as an architect of peace.

-

Ukraine in 2024: When War Fatigue Replaces the Search for Peace

By 2024, the war in Ukraine has entered a phase that is politically uncomfortable but strategically revealing. The initial sense of urgency that once dominated international discourse has gradually been replaced by something quieter and more dangerous: war fatigue. This fatigue is no longer confined to societies or media cycles; it has begun to shape diplomatic priorities and policy choices.

When the conflict escalated in February 2022, Ukraine quickly became a central reference point for debates on sovereignty, deterrence, and international order. Throughout 2023, the focus shifted toward sustaining military support and preserving strategic unity among allies. In 2024, however, the conversation has subtly changed. The central question is no longer how the war might end, but how long it can be managed without a decisive political resolution.

War fatigue rarely presents itself openly. It appears through delays, cautious phrasing, and an increasing reliance on “realistic expectations.” Diplomatic statements grow repetitive, peace initiatives remain abstract, and discussions of ceasefires are deferred in favor of maintaining an uneasy status quo. Endurance replaces imagination, and stability is mistaken for progress.

From a peace-oriented perspective, this shift is deeply concerning. Fatigue does not open pathways to peace; it normalizes prolonged violence. As the costs of war become familiar, the incentive to pursue difficult diplomatic compromises weakens. The conflict ceases to be treated as an emergency requiring resolution and instead becomes a permanent feature of international politics.

What makes this moment particularly critical is the uneven distribution of war fatigue. While political and strategic debates revolve around sustainability and risk management, civilians continue to experience the war as an ongoing reality. Displacement, infrastructure destruction, and insecurity persist, even as global attention gradually diffuses.

In 2024, discussions surrounding Ukraine increasingly center on capacity—how much support can be maintained, how long unity can last, and how escalation can be avoided. These questions are legitimate, but insufficient. A strategy focused solely on managing risk, without articulating a credible vision for peace, risks prolonging the instability it claims to contain.

This is not an argument for rushed or superficial negotiations. Sustainable peace cannot emerge from exhaustion alone, nor can it be imposed through impatience. Yet peace is equally unlikely to materialize through indefinite postponement. When diplomatic energy is consumed entirely by managing the present, the future quietly disappears from the agenda.

The implications extend beyond Ukraine. If war fatigue becomes an accepted feature of international crises, it establishes a precedent in which conflicts are endured rather than resolved. War ceases to be seen as a failure of politics and becomes an ordinary condition of global order.

Ultimately, the defining challenge of 2024 is not the absence of diplomatic tools, but the absence of urgency behind them. Peace requires sustained political will. Without it, fatigue hardens into policy—and war becomes routine.

-

Gaza War and the Collapse of Moral Consistency in International Politics

What has unfolded in Gaza since late 2023 is not only a humanitarian catastrophe or a prolonged military confrontation. It is also a moment of moral exposure for the international system. The violence itself is devastating, but what lingers more painfully is the uneven way in which that violence is acknowledged, justified, or quietly ignored.

In theory, international politics claims to be guided by universal principles: the protection of civilians, proportionality, humanitarian law, and the pursuit of peace. In practice, Gaza has revealed how conditional those principles can become once they collide with strategic interests, alliances, and political convenience. The problem is no longer the absence of norms, but the selective way they are applied.

Civilian suffering in Gaza has been widely documented. The scale of destruction, displacement, and human loss has been impossible to conceal. Yet the dominant international response has oscillated between cautious statements, delayed concern, and carefully worded silences. Calls for restraint often lack urgency, while appeals for ceasefires are diluted by political calculations. This gap between declared values and actual behavior is not accidental; it reflects a deeper erosion of moral consistency in global politics.

What is most troubling is how quickly civilian suffering becomes a secondary issue once the language of security takes over. The framing shifts from human lives to strategic narratives, from humanitarian urgency to geopolitical positioning. In this environment, peace is no longer treated as an immediate necessity but as a distant, abstract objective—something to be discussed after “security conditions” are met, even as those conditions remain undefined.

From a peace-oriented perspective, this logic is deeply flawed. Peace cannot be postponed indefinitely in the name of security, especially when security itself is producing widespread civilian harm. When international actors tolerate this contradiction, they do not remain neutral; they actively contribute to the normalization of prolonged violence. Silence, in such moments, is not a passive stance—it is a political choice.

The Gaza war has also exposed the limits of credibility in international diplomacy. When similar humanitarian crises are met with strong language in some contexts and cautious ambiguity in others, the idea of a rules-based order loses its meaning. For societies watching from the outside, this inconsistency reinforces the perception that international law is not universal, but negotiable.

This is not an argument about taking sides in a conflict. It is an argument about taking sides with civilians. A peace-driven position does not require moral perfection, but it does require moral clarity. If the protection of civilians is truly a universal principle, then it cannot depend on geography, identity, or political alignment.

Ultimately, Gaza is forcing the international community to confront an uncomfortable question: is peace still a guiding objective, or has it become a rhetorical placeholder—invoked when convenient, ignored when costly? The answer to that question will shape not only the future of Gaza, but the credibility of international politics itself.

-

“How Did Russia’s Wagner Crisis Unfold?

Summary of the Event and Its Development

On 23 June 2023, Yevgeny Prigozhin, leader of the Wagner Group, released a video criticizing the inadequate logistical support on the front line and calling for the government to be held accountable “for justice.” Prigozhin claimed that approximately 25,000 fighters were ready to march from Rostov-on-Don toward Moscow and began what he described as a march for retribution.

The insurgents seized control of the area around Rostov by midday on Saturday but were unable to reach Moscow. Through the mediation efforts of Alexander Lukashenko, an agreement was reached under which Wagner forces withdrew; the Kremlin announced that Prigozhin would be exiled to Belarus and that charges against him would be dropped. Thus, the 36-hour uprising ended without bloodshed and did not escalate into nationwide conflict.

State Capacity and Regime Stability

While the suppression of the revolt challenged the perception of weakness highlighted by some observers, the state emerged relatively strong from this crisis. The regime demonstrated its capacity for control by resolving the mutiny without major clashes, and Wagner fighters were partially disarmed before being relocated to Belarus. Following Prigozhin’s death, all Wagner personnel were required to swear allegiance to Russia, effectively reintegrating the private force into the state’s security framework.

A significant segment of the military remained loyal to the government, while several commanders linked to Wagner were quietly removed. Putin seized the moment to strengthen internal security by authorizing new heavy weapon allocations to the National Guard, bolstering deterrence against future uprisings. While no widespread unrest materialized, the Kremlin maintained—and in some respects reinforced—its political standing.

Nonetheless, the mutiny undeniably impacted the regime. Analysts highlighted internal factional tensions within the Kremlin and argued that Putin’s authority suffered reputational damage. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken described the uprising as creating “real cracks” in the leader’s authority, while French President Emmanuel Macron emphasized that divisions within the Russian military exposed its structural fragility.

Several Western analysts wrote that the events raised serious questions about the long-term stability of the Putin regime. Some warned that failure to decisively punish Prigozhin could endanger Putin’s position, while others argued that although the system held, it was clearly more vulnerable than before.

Geopolitical Implications

The Wagner mutiny had limited direct impact on the Ukrainian battlefield. Analysts noted that Wagner units were primarily organized as specialized assault forces and had withdrawn from the Bakhmut operation shortly before the mutiny, meaning the uprising produced no immediate change in trench dynamics.

Nevertheless, the incident created diplomatic ripple effects in Russia’s foreign relations. China framed the developments as “Russia’s internal affairs” and expressed support for Moscow’s efforts to maintain stability. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs reaffirmed its backing for Russia’s pursuit of national unity, while Chinese strategists viewed the crisis as an internal split within the Kremlin and warned that a weakened Putin could undermine China’s long-term strategic positioning.

Meanwhile, NATO states debated the broader implications. Statements from France and the United States reinforced perceptions of vulnerability within the Russian military, while many analysts remained cautious about how these weaknesses would shape Moscow’s future foreign policy behavior. Ultimately, the Wagner crisis presented allies and adversaries alike with new questions about the resilience and internal coherence of Putin’s rule.

The Role of Private Military Companies Within the State

Private military companies (PMCs) are typically employed by states to support military objectives. Russia’s Wagner Group, formed during the 2014 Donbas campaign, has operated as a proxy force across Ukraine, Syria, Libya, and parts of Africa. Despite lacking official legal status, Wagner functioned as a paramilitary extension of the Kremlin, financed and directed with political objectives in mind.

However, the inherently flexible and profit-driven nature of PMCs can produce significant security risks. Experts argue that forces capable of acting independently of state authority must be replaced—or strictly subordinated—to regular armed forces, supported by compulsory service where applicable.

In many respects, the Wagner uprising represents the first instance of a private military company launching a mutiny in modern Russian history. This episode underscores the strategic consequences of relying on semi-autonomous paramilitary groups and highlights the critical importance of strict oversight within state security structures.

-

India–Canada Diplomatic Crisis (2023)

Parties Involved and the Root Causes of the Crisis

In 2023, diplomatic tensions sharply escalated between Canada and India. The core trigger of the crisis was the killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar on June 18, 2023, in front of a Sikh temple in Surrey, British Columbia. Nijjar was a Sikh leader designated by the Indian government as a “separatist terrorist.” Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced on September 18, 2023, during an emergency parliamentary session, that Canada was actively investigating “credible allegations” linking Indian intelligence agents to Nijjar’s killing. India rejected these accusations as “absurd and politically motivated,” accusing Trudeau of attempting to damage India’s reputation. Despite historically strong ties and a large Sikh diaspora in Canada, the Nijjar murder created a deep trust crisis between the two countries.

Development of the Crisis and Key Dates

- June 18, 2023 – Assassination of Nijjar: Nijjar was shot dead outside a Sikh temple in Surrey. As a prominent advocate for an independent Sikh state (“Khalistan”), he had long been on India’s terror watch list. While India viewed him strictly as a militant extremist, Canada suspected the involvement of foreign state agents.

- September 1, 2023 – Suspension of Trade Talks: As tensions increased, Canada unexpectedly paused negotiations on a free trade agreement with India. Though no official link was stated, Canadian media indicated the decision was connected to the Nijjar case.

- September 9–10, 2023 – G20 Summit Tensions: During the G20 Summit in India, relations visibly deteriorated. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi held bilateral talks with many leaders but did not meet with Trudeau. Prior to this, Trudeau had expressed frustration that allies—especially the United States—did not publicly support Canada’s allegations during the summit.

- September 18, 2023 – Trudeau’s Parliamentary Accusation: Trudeau publicly declared that Canada was investigating credible intelligence suggesting Indian involvement in Nijjar’s assassination. He described any foreign government’s involvement in such a killing as a “grave violation of sovereignty.” On the same day, Canada expelled a senior Indian intelligence official, and India promptly expelled a senior Canadian diplomat in retaliation.

- September 19, 2023 – Reciprocal Diplomatic Measures: India dismissed Trudeau’s claims as “baseless and deliberate.” Both countries summoned each other’s ambassadors and expelled top diplomats. India additionally demanded a reduction of Canada’s diplomatic staff on its territory.

- September 21, 2023 – Suspension of Visa Services: India suspended new visa applications for Canadian citizens, citing security threats, and demanded that Canada downsize its diplomatic presence. Indian media also reported social media threats against Indian diplomats in Canada. Canada began withdrawing diplomatic staff as the investigation continued.

- October 19, 2023 – Canada Withdraws Diplomats: After India threatened to revoke diplomatic privileges, Canada pulled back 41 of its diplomats from India. Ottawa asserted that New Delhi’s demands violated the Vienna Convention. India countered by demanding equal diplomatic staffing levels.

- October 25, 2023 – Partial Resumption of Visa Services: India partially resumed visa services for certain categories ahead of the wedding season. However, officials emphasized that this did not signal full normalization.

- November 22, 2023 – U.S. Developments: The United States revealed that it had prevented a separate plot targeting Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, a close associate of Nijjar. Washington warned New Delhi as investigations into international links continued, adding a global dimension to the crisis.

International Reactions and Global Impact

India repeatedly rejected all accusations and accused Canada of harboring and tolerating extremist elements within its borders. Canada, on the other hand, warned that foreign interference in domestic affairs represented an unacceptable breach of national sovereignty. The crisis deeply alarmed Western allies, particularly the United States and the United Kingdom. Both urged India to reconsider its actions regarding diplomatic staff reductions and warned of possible violations of international diplomatic norms.

Canada briefed its intelligence allies within the “Five Eyes” alliance. The United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia expressed “serious concern,” but avoided direct condemnation of India due to its strategic importance against China. During the G20 Summit, Western leaders were notably reluctant to directly confront India on the issue.

Diplomatic Measures and Retaliation

India suspended visa services for Canadian citizens, while Canada recalled dozens of diplomats from India. Both sides declared senior diplomatic officials “persona non grata.” India cited security concerns regarding its consulates in Canada. Canada temporarily suspended consular services in several Indian cities and experienced visa processing delays.

Trade relations were also affected, as both sides froze free trade negotiations and canceled economic forums. These measures functioned more as diplomatic pressure tools than legal sanctions—no financial or military sanctions were imposed.

Statements by Political Leaders

Prime Minister Trudeau declared in Parliament that any involvement by a foreign government in a murder on Canadian soil constitutes a “serious violation of sovereignty.” The Indian government categorically denied all accusations. India’s Ministry of External Affairs labeled Trudeau’s claims “absurd and deliberate,” and criticized Canada for failing to suppress separatist activity.

Indian officials justified visa suspensions by citing alleged security risks to their diplomatic missions. The United Kingdom further emphasized that India’s actions against Canadian diplomats conflicted with basic principles of international diplomatic law.

Consequences and Ongoing Developments

By the end of 2023, no full diplomatic normalization had taken place. While India partially resumed visa services, experts described the situation as one of the deepest crises in the history of India–Canada relations. Trade, academic cooperation, and civil mobility suffered significant setbacks.

The Nijjar investigation continues, and with India’s 2024 elections approaching, no clear diplomatic resolution appears imminent. The disruption of a second assassination plot in the United States underlined the international ramifications of the crisis. The prevailing view is that only a long-term confidence-building diplomatic process can resolve the dispute.

-

The Resumption of U.S.–China Diplomacy in 2023: A Measured Step Toward Global Trust

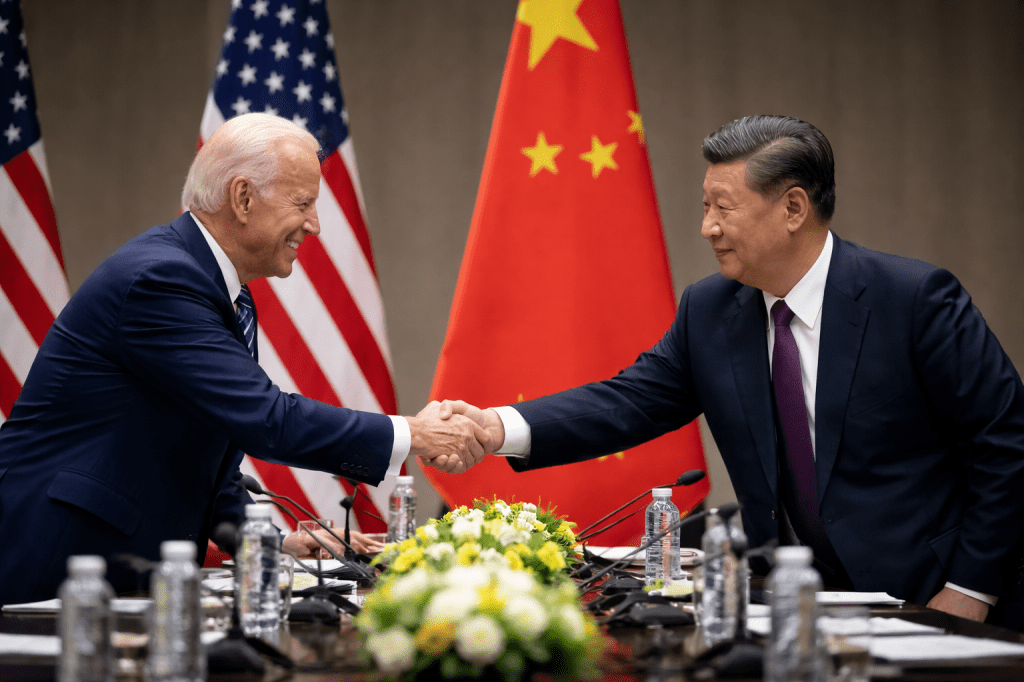

In an international system increasingly shaped by hardened rivalries, fragmented trust, and rapid escalation risks, the revival of diplomatic engagement between the United States and China in 2023 deserves to be read as more than routine statecraft. It is not a dramatic reconciliation, nor a sudden shift in strategic competition. Yet, precisely because today’s global atmosphere is saturated with suspicion, even cautious diplomatic steps carry disproportionate value. Over the past several years—especially after 2018—U.S.–China relations were often defined by trade disputes, technology restrictions, heightened Indo-Pacific security dynamics, and intensifying rhetoric. In such a climate, communication channels tend to narrow, crisis perception becomes distorted, and the risk of miscalculation grows. For this reason, the return of sustained diplomatic contact in 2023 should be understood as an investment in predictability—an essential ingredient for global peace.

Key Dates That Marked the Diplomatic Reopening

A notable signal came with Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to Beijing in June 2023. After a prolonged period in which high-level exchanges had repeatedly stalled, this visit helped restore a basic diplomatic rhythm. The significance was not that tensions disappeared—but that both sides acknowledged the practical necessity of keeping lines open.

The process continued with Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s visit in July 2023, followed by Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo’s trip in August 2023. These engagements, focused on economic and commercial issues, reinforced a simple reality: geopolitical rivalry between the world’s two largest economies inevitably shapes global markets, supply chains, and the strategic calculations of third countries. Diplomacy here becomes not an act of goodwill alone, but a stabilizing mechanism for the broader international environment.

The most consequential moment arrived with the Biden–Xi meeting in San Francisco in November 2023. Beyond symbolism, the meeting carried practical implications, including steps toward restoring military-to-military communication—an area that matters profoundly when the global system is already vulnerable to misunderstandings and unintended escalation.

Why This Matters for Peace and Confidence

Diplomacy does not require friendship. Its primary purpose—especially between strategic competitors—is to prevent rivalry from sliding into uncontrolled confrontation. In that sense, the 2023 diplomatic reopening can be seen as a modest but meaningful contribution to global peace. It reduces ambiguity, clarifies intentions, and creates room for crisis management.

I approach this development with a deliberately good-faith lens. Not because structural competition has vanished—clearly it has not—but because the world has too much to lose when the strongest actors communicate only through pressure, deterrence, and public messaging. When dialogue collapses, fear fills the gap. When dialogue returns, even partially, it restores a minimum level of strategic restraint.

Importantly, the benefits of U.S.–China diplomacy are not confined to Washington and Beijing. Third countries, regional organizations, and global markets all operate under the shadow of U.S.–China tensions. When those tensions are managed through direct contact, the international system gains breathing space. Global peace is sometimes preserved not by grand agreements, but by preventing major crises from erupting.

Conclusion

The diplomatic engagement reactivated in 2023 did not resolve the deep-rooted disagreements between the United States and China. But it signaled something increasingly rare: a recognition that rivalry must be governed, not glorified. In an era when good-faith gestures are scarce and trust is fragile, keeping diplomacy alive is itself a strategic contribution to peace.

For those of us who still prioritize an international order shaped by stability and confidence, the resumption of U.S.–China diplomatic contact in 2023 should be treated as a cautious yet valuable step in the right direction.

-

Analysis of China–Russia Joint Military Exercises in the 2018–2023 Period

Introduction

Over the five-year period from 2018 to September 2023, the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation have conducted a series of extensive joint military exercises, elevating their security cooperation to an unprecedented level. These exercises, which have the potential to alter the post–Cold War balance of power, have offered both countries an opportunity to demonstrate their military capabilities and intentions on a global scale. As the size of the exercises, the diversity of forces involved, and their geographical reach have steadily expanded, the geopolitical messages they convey have also become more explicit.

This report analyzes, with an analytical approach, the military dimensions of the major exercises carried out jointly by China and Russia in this period, the strategic signals they have sent, and their regional effects stretching from the Asia-Pacific to Central Asia and Europe. By evaluating the timing, geographical location, scope of the exercises, and international reactions, it seeks to reveal how this rapprochement is reflected in the architecture of global security.

Military Dimension and Scope of the Exercises

Vostok-2018 Exercise (September 2018)

The Vostok-2018 (East-2018) strategic exercise, held by Russia on 11–17 September 2018, was announced as the largest military exercise since the Soviet Union’s Zapad maneuvers of 1981. According to official statements, the plan called for the participation of 300,000 Russian troops, 36,000 armored vehicles, and more than 1,000 aircraft, aiming at an unprecedented show of force on Russian territory. Even though actual participation turned out somewhat smaller, the most striking aspect of this exercise was the inclusion of China for the first time.

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) joined Vostok-2018 with approximately 3,200 personnel, 900 armored vehicles, and 30 combat aircraft, making it the first foreign force to take part in a Russian domestic strategic exercise in the post-Soviet era. The exercise was conducted across Siberia and Russia’s Far East and included large-scale combat scenarios against a force modeled on NATO. Chinese units deployed alongside Russian forces at the Tsugol training range, carrying out joint missions such as air–ground coordination, airborne operations, and artillery fire support.

Vostok-2018 tested the Russian army’s command-and-control capabilities, while for China it offered the opportunity to observe Russia’s combat experience in Syria and gain practice in large-scale joint operations. At the same time, this massive exercise signaled that Moscow and Beijing no longer regarded each other as direct threats but were instead prepared to act together against a common adversary—represented in the scenario by “Western” forces.

Tsentr-2019 Exercise (September 2019)

Held on 16–21 September 2019 in Russia’s Orenburg region and on ranges in Central Asia, the Tsentr-2019 (Center-2019) exercise stood out with its multinational participation. Russia joined the exercise with around 128,000 troops, while China, India, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan—members of the SCO/CSTO framework—also took part.

The PLA deployed around 1,600 troops from the Western Theater Command, along with Type-96A main battle tanks, J-11 fighter jets, JH-7A fighter-bombers, H-6K strategic bombers, Z-10 attack helicopters, and Y-9 and Il-76 transport aircraft. Notably, the Chinese Air Force used live munitions on Russian soil for the first time, with H-6K strategic bombers striking ground targets; 23 Chinese aircrews took part in the joint operations.

Although the exercise was officially framed around counter-terrorism, a significant portion of the scenario focused on repelling a conventional enemy state and conducting large-scale counter-offensive operations. In this sense, Tsentr-2019 went beyond a counter-terrorism drill in Central Asia and functioned as a rehearsal for joint warfare by major powers. The exercise’s multinational character showed that Moscow and Beijing could assume a leadership role in the region’s security architecture, while the presence of both India and Pakistan under the same umbrella symbolized the search for geopolitical balance by two rival powers within the Russia–China axis.

Kavkaz-2020 Exercise (September 2020)

In September 2020, despite the constraints of the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia conducted the Kavkaz-2020 (Caucasus-2020) exercise as part of its annual series of strategic drills. After holding six joint exercises with China in 2019, the Moscow–Beijing duo was able to come together in person only for this exercise in 2020, the pandemic year.

The exercise was carried out in Russia’s Southern Military District, particularly around the Kapustin Yar range in Astrakhan, and included scenarios spanning the South Caucasus and the Caspian basin. China participated by sending units from the 76th Group Army of the Western Theater Command. Armenia, Belarus, Myanmar and Pakistan were also invited, giving the exercise a distinctly multinational character.

Since 2018, Russia has started to include not only Belarus but also China and several other partner states in its strategic-level exercises, which reflects Moscow’s growing confidence in Beijing. However, Chinese forces’ involvement in Kavkaz-2020 was largely limited to show-of-flag roles and restricted joint operations. In several sensitive phases where new tactical concepts were tested, the Russian army chose to proceed without Chinese observers. This indicates that, despite deeper cooperation, Moscow still feels the need to safeguard some of its strategic secrets.

Zapad/Interaction-2021 Exercise (August 2021)

Held on 9–13 August 2021 in China’s Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and known in Chinese sources as “Xibu/Lianhe-2021” (West/Interaction-2021), this exercise marked a milestone as the first joint military drill conducted on Chinese soil by China and Russia. Roughly 10,000–13,000 troops from the PLA Western Theater Command and the Russian Eastern Military District participated.

The scenario, under the theme of “maintaining regional security and stability,” focused on testing capabilities for joint reconnaissance, early warning, electronic warfare and target neutralization through combined firepower. Strikingly, Russian troops used modern Chinese weapons and equipment during the exercise; systems such as the newly introduced Type-95 integrated air-defense missile system were operated by Russian soldiers.

For its part, China for the first time deployed J-20 stealth fighter jets and Y-20 strategic transport aircraft in an exercise, while the Russian Air Force participated with Su-30 fighter jets. Deep integration was achieved in command and control: a three-tier, bilingual (Chinese–Russian) joint command center was established for the exercise, along with real-time intelligence-sharing networks.

The operational phase of the exercise was planned in four stages: detection and neutralization of enemy forces and positions; breaking the defense line through intense artillery and air bombardment; deep offensive operations conducted by airborne and special forces; and finally, the complete destruction of the enemy. During these phases, under the cover of J-20 fighters, Chinese H-6K and JH-7A bombers destroyed designated targets, while multiple rocket launchers and 155mm howitzers delivered hundreds of tons of munitions, collapsing enemy defenses.

Subsequently, Chinese airborne units and armored personnel carriers were airlifted to the field by Y-20 and Y-9 aircraft, and Russian and Chinese special forces teams—supported by helicopters—seized critical points behind enemy lines. At the closing ceremony, the defense ministers of both countries attended together and reaffirmed their commitment to deepen military cooperation in various domains, including counter-terrorism.

Zapad/Interaction-2021, as the first major exercise hosted and partly led by China, symbolized the level of mutual trust and integrated operational capability that the two armed forces had reached.

Vostok-2022 Exercise (September 2022)

While the war in Ukraine was ongoing, Russia conducted the Vostok-2022 strategic exercise in the Far East in September 2022 as part of its four-year training cycle. Compared to Vostok-2018, however, Russia’s capacity to participate had clearly declined. Official figures stated that about 50,000 troops, 140 aircraft and 5,000 pieces of military equipment took part—significantly below the 300,000 troops and 1,000 aircraft announced for 2018. This reduced scale was widely linked to the strain placed on the Russian military by the Ukrainian front since February 2022.

Despite this, Russia invited China again, seeking to demonstrate that their military rapprochement had not been interrupted. The PLA participated in Vostok-2022, held on 1–7 September 2022, with land, air and naval elements. China deployed more than 2,000 personnel, armored units and air assets to the Far East; additionally, for the first time, the Chinese Navy joined naval drills in the Sea of Japan alongside the Russian Pacific Fleet.

In this framework, the two navies executed scenarios such as securing sea lines of communication, anti-submarine warfare and air-defense operations. The exercise covered a wide geographic area stretching from Chukotka to the Sea of Japan, and Chinese and Russian forces conducted synchronized maneuvers both on land and at sea.

It was also notable that, beyond China and Russia, countries such as India, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Syria—along with several other Asian, African and Latin American states—took part as observers or troop contributors, bringing the total to around 14 participating countries. Moscow thus aimed to show that, despite attempts to isolate it over the Ukraine war, it still retained international partners. Overall, Vostok-2022 was perceived as a show of force emphasizing that Russia–China military cooperation continued even under wartime conditions, while sending a message to regional rivals like Japan and the United States that the two countries could project power on multiple fronts simultaneously.

Northern/Interaction-2023 Naval Patrol (July–August 2023)