-

U.S. Military Intervention in Venezuela: Law, Use of Force, and the International System

INTRODUCTION

The military operation carried out by the United States in Venezuela and the subsequent capture of President Nicolás Maduro are regarded as one of the most controversial interventions in contemporary international relations, with far-reaching consequences. Conducted unilaterally and without explicit authorization from the United Nations Security Council, this intervention has reignited global debates over state sovereignty, the use of force, and the limits of international law.

While the operation has been justified by the United States within the frameworks of security, criminal justice, and strategic necessity, it has been characterized by many states and international organizations as a violation of sovereignty, an unlawful use of force, and a dangerous precedent for the international system. These contrasting approaches make it necessary to examine the intervention not merely as a military or technical operation, but together with its legal, political, and geopolitical dimensions.

This article aims to analyze the U.S. military operation in Venezuela through a multidimensional analytical framework. In this context, it first examines in detail the sequence and implementation of the operation, followed by an analysis of the reasons behind the operation. It then assesses the international reactions to the intervention, highlighting the divisions that emerged at the global level. In the subsequent section, the operation is evaluated from the perspectives of international law, U.S. domestic law, and Venezuelan domestic law, and its legal framework is discussed. Finally, the article addresses the precedent value of the intervention and its long-term implications for the international system.

Within this framework, the study seeks to demonstrate that the Venezuela case is not merely a bilateral crisis, but a development with broader and structural consequences for the future of the international order.

SEQUENCE AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE OPERATION

The military operation carried out by the United States against Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela constituted a pre-planned and coordinated multi-phase intervention. The operation was executed during the night of 2–3 January 2026 through a synchronized process involving military, security, and intelligence assets.

Initiation of the Operation

The final political authorization for the operation was granted on Friday night, 2 January 2026, at approximately 22:45–23:00 (U.S. Eastern Time – EST). Following this authorization, U.S. Armed Forces and federal security agencies were mobilized simultaneously, and the operation was effectively launched on Venezuelan territory in the early hours of Saturday, 3 January 2026.

The choice to conduct the operation between midnight and early morning hours reflects a classic military preference aimed at maximizing surprise and limiting the target area’s early warning and response capabilities.

Military Strikes and Area Control

During the initial phase of the operation, between 00:00 and 02:00 (EST) on 3 January 2026, air strikes were carried out against selected military targets in and around Caracas. The objective at this stage was to suppress the Venezuelan security forces’ air defense, command, and coordination capabilities and to rapidly establish operational control over the area.

Within the same time window, power outages and communication disruptions were reported in certain parts of Caracas. This phase is assessed as an area-shaping stage, conducted prior to the direct apprehension phase of the operation.

Movement Toward Maduro’s Location

Simultaneously with the air strikes, mixed teams composed of U.S. special forces and federal security elements were directed toward a secure location believed to be hosting Nicolás Maduro. It is reported that these units reached the site at approximately 01:00 (EST) on 3 January 2026, during which limited armed contact occurred.

At this stage, one of the helicopters reportedly sustained minor damage but remained operational and continued its mission.

Apprehension and Custody Phase.

Following entry into the secure location, Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, were taken into custody within the 01:00–02:00 (EST) time window. According to U.S. accounts, the apprehension did not escalate into prolonged fighting, and this phase of the operation was completed relatively quickly.

This outcome underscores the critical role of pre-operation intelligence superiority and precise timing.

Exit from Venezuelan Airspace and Maritime Phase

After the apprehension, special units extracted Maduro and his wife from Caracas by helicopter and transported them out of Venezuelan airspace between 03:00 and 03:30 (EST). At approximately 03:20 (EST), the helicopters reached open waters, where contact was established with U.S. Navy assets.

At this point, the operational phase on Venezuelan territory effectively ended, and the process transitioned into a maritime transfer phase.

Public Announcement and Initial Political Reactions

Immediately following the completion of the operation, the first official statement by the U.S. President was released to the public around 04:20–04:30 (EST) on 3 January 2026. With this announcement, the operation was formally confirmed and disclosed to the international community.

In parallel, Venezuelan authorities issued statements on the same day characterizing the incident as a “kidnapping” and declaring that it constituted a severe violation of state sovereignty.

Transfer to the United States and Transition to Judicial Proceedings

Following the maritime phase, Maduro and his wife were transferred to the United States during the evening hours of 3 January 2026. With this transfer, the operation ceased to be a military intervention and transitioned into a legal process under the jurisdiction of the U.S. federal judicial system. In the days that followed, it was reported that Nicolás Maduro would be brought before U.S. federal courts.

REASONS BEHİND THE OPERATION

1. Counter-Narcotics Efforts and the National Security Narrative

When presenting the operation against Venezuela to the public, the U.S. administration has highlighted the fight against drug trafficking as one of its primary justifications. According to Washington, Venezuela has for years become one of the key transit hubs along the drug trafficking routes extending from South America to North America. This situation has been framed not merely as an issue of combating organized crime, but as a matter of U.S. national security.

- Within this narrative, drug trafficking is described as:

- A threat to public health in the United States,

- A major source of financing for armed and illicit groups,

- A security risk that erodes state capacity.

Accordingly, the issue is removed from the realm of ordinary criminal law and repositioned within a securitized policy framework.

2. The “Narco-State” and “Narco-Terrorism” Framework

In U.S. political and legal discourse, Venezuela has increasingly been portrayed as a “narco-state,” while Nicolás Maduro has been framed not merely as a political leader, but as an actor allegedly embedded within transnational criminal networks. This narrative enables Maduro to be removed from the status of a legitimate head of state and redefined as a criminal actor.

Within this framework, the concept of “narco-terrorism” combines:

- Drug trafficking,

- Cooperation with armed organizations,

- Criminal structures embedded within state institutions.

By merging these elements, the concept functions as a political narrative that legitimizes the use of military and security-based instruments.

3. U.S. Federal Judicial Process: Criminal Cases Against Nicolás Maduro

One of the central elements cited by the United States in explaining and justifying the operation has been the existence of ongoing federal criminal proceedings against Nicolás Maduro within the U.S. judicial system.

However, these indictments constitute criminal proceedings under U.S. domestic law and do not, from the perspective of international law, automatically provide legal authorization for military intervention.

4. Policy of Non-Recognition of Regime Legitimacy

The United States has for a prolonged period explicitly stated that it does not recognize the Maduro administration as the legitimate government of Venezuela. This policy of non-recognition plays a significant role in the justification of the operation. According to Washington, the leader of a government that is not recognized as legitimate:

- Cannot benefit from head-of-state immunity,

- Possesses a contested status under international law,

- May become the target of criminal investigations.

Although this approach does not produce binding legal consequences under international law, it allows the U.S. to frame the operation domestically not as an “attack against a sovereign state,” but as an intervention against an unlawful structure.

5. Domestic Politics and the Congress–Executive Balance

U.S. domestic politics has also played a decisive role among the reasons behind the operation. The Venezuela file has long been an area in which:

- Both political parties in Congress have adopted a hardline stance,

- Latin American diaspora communities particularly in Florida have exerted political influence,

- The boundaries of presidential authority have been actively tested.

Within this context, the operation is associated not only with foreign policy or security rationales, but also with efforts to demonstrate political resolve, project toughness, and expand the executive branch’s room for maneuver.

6. Geopolitical Signaling and Deterrence

Finally, geopolitical signaling and deterrence constitute another core motivation behind the operation. From the U.S. perspective, Venezuela is not merely a Latin American country, but also a state that has developed close relations with actors such as Russia, China, and Iran.

In this context, the operation can be interpreted as part of a broader strategic framework aimed at:

- Reasserting U.S. power projection in Latin America, traditionally viewed as its sphere of influence,

- Drawing clear boundaries for rival global actors,

- Delivering a message of “vulnerability” and demonstrated reach to regimes perceived as hostile.

INTERNATIONAL REACTIONS ON THE U.S. MILITARY OPERATION IN VENEZUELA

China

Argentina

Argentine President Javier Milei openly signaled support for the outcome of the U.S. operation in Venezuela through an official X post, writing: “Liberty advances. ¡Viva la libertad, carajo!”

Panama

Panamanian President José Raúl Mulino, in an official statement on developments in Venezuela, reiterated his government’s support for democratic legitimacy and the will of the people. Mulino emphasized that Edmundo González was elected through legitimate elections and that Panama supports a peaceful and orderly transition process.

Russia

Mexico

Brazil

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva condemned the U.S. bombardment of Venezuela and the capture of Nicolás Maduro, stating that these actions crossed an “unacceptable line” and amounted to a severe attack on Venezuela’s sovereignty.

Colombia

Colombian President Gustavo Petro described the U.S. operation in Venezuela as a direct attack on sovereignty. He called for the immediate convening of the United Nations and the Organization of American States, arguing that the crisis must be resolved through diplomacy rather than military means.

Cuba

Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel described the U.S. military action against Venezuela as a “criminal attack” and an act of “state terrorism,” warning that it undermines the “Zone of Peace” status of Latin America and the Caribbean. He urged the international community to respond urgently, arguing that such interventions severely threaten regional peace.

Iran

France

French Foreign Minister Jean-Noël Barrot stated that the U.S. military operation violated international law and the UN Charter’s principle of non-use of force. He emphasized that no political solution can be imposed externally and reiterated the importance of respecting peoples’ right to self-determination.

Germany

Germany stated that it was closely monitoring the situation. The Foreign Ministry urged all parties to avoid escalation, respect international law, and pursue a political solution. Chancellor Friedrich Merz added that the legal assessment of the operation is complex and should be addressed within an international legal framework.

Spain

Canada

United Kingdom

British Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer stated that the United Kingdom was not involved in the U.S. operation in Venezuela and emphasized that protecting international law and ensuring the safety of British citizens remain key priorities. He noted that developments are being closely followed while awaiting full clarification of the facts.

Ukraine

Ukrainian Foreign Minister Andrii Sybiha stated that Ukraine does not recognize Nicolás Maduro’s leadership as legitimate and reaffirmed Ukraine’s support for democracy, human rights, and peaceful solutions grounded in international law.

Greece

Greece’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that it is closely monitoring developments in Venezuela in coordination with EU partners. Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis criticized Maduro’s long-standing authoritarian rule while emphasizing the need to focus on a peaceful, democratic transition rather than a legal assessment of the military action.

Türkiye

Israel

Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar welcomed and praised the U.S. operation and the capture of Nicolás Maduro, describing the United States as the “leader of the free world.” He characterized the Maduro government as illegal and repressive and expressed hope that the Venezuelan people’s democratic rights would be upheld.

India

India adopted a cautious stance, stating that it is closely monitoring developments, urging restraint, and emphasizing the importance of respecting international law. The Ministry of External Affairs did not issue a separate written press release on the matter.

South Africa

South Africa’s Department of International Relations and Cooperation opposed the use of force and unilateral interventions, stressing respect for the UN Charter and international law and calling for dialogue and diplomacy.

United Nations

The United Nations described the U.S. military operation as deeply concerning. UN Secretary-General António Guterres urged all parties to respect international law and the UN Charter and called for immediate de-escalation. UN human rights officials emphasized the protection of civilians, while the UN Security Council was reported to be moving to address the situation.

LEGAL ASSESSMENT

1. Assessment from the Perspective of International Law

From the standpoint of international law, the use of military force by the United States on Venezuelan territory and the forcible capture of the head of state clearly conflict with fundamental legal norms. This assessment can be made on the basis of the following points:

- Prohibition of the Use of Force (UN Charter Art. 2/4): The use of force by states against the territorial integrity or political independence of another state is prohibited. The military operation against Venezuela constitutes a direct violation of this prohibition.

- Absence of the Conditions for Self-Defense (UN Charter Art. 51): As there has been no armed attack originating from Venezuela against the United States, the exception of self-defense is not legally applicable.

- Lack of United Nations Security Council Authorization: There is no United Nations Security Council decision or authorization regarding the operation. This renders the intervention unauthorized under international law.

- Violation of the Principles of Sovereignty and Non-Intervention: The forcible capture of a head of state by a foreign power amounts to the suspension of the sovereign powers of the state and direct intervention in the regime.

- Violation of the Personal Immunity of Heads of State: Under customary international law, serving heads of state enjoy immunity from the jurisdiction of foreign states. Criminal allegations do not remove this immunity.

- Bypassing of International Criminal Justice: The criminal responsibility of heads of state is addressed through international judicial mechanisms. A unilateral military apprehension bypasses this process. As a result, from the perspective of international law, this intervention constitutes unlawful use of force, a serious violation of sovereignty, and a prohibited intervention.

2. Assessment from the Perspective of United States Domestic Law

From the perspective of U.S. domestic law, the operation presents a more complex and controversial framework.

- Lack of Congressional Authorization: There is no specific and explicitly named congressional authorization (AUMF) for the arrest of Nicolás Maduro or for the use of military force in Venezuela.

- Broad Interpretation of the AUMFs: The U.S. administration seeks to justify the operation by broadly interpreting the 2001 and 2002 AUMFs within the framework of counterterrorism. However, these authorizations do not explicitly cover a military operation against the leader of a sovereign state.

- Limited Judicial Basis: Indictments issued by U.S. federal prosecutors and the “Rewards for Justice” program do not confer authority to conduct an extraterritorial apprehension through the use of military force. U.S. courts cannot issue orders for military operations on the territory of a foreign state.

- Presidential Authority and Constitutional Limits: While the President’s commander-in-chief authority is extensive, the use of military force at a level that creates inter-state conflict falls, under the Constitution, within the authority of Congress. For these reasons, the operation rests on a legally controversial foundation even within U.S. domestic law, particularly with regard to constitutional limits on authority.

3. Assessment from the Perspective of Venezuelan Domestic Law

From the perspective of Venezuelan domestic law, the situation is clear and not open to dispute:

- Violation of the Constitutional Order: The head of state may be removed from office only through constitutional mechanisms within the country. Intervention by a foreign military force constitutes the forcible overthrow of the constitutional order.

- Attack on Sovereignty and National Independence: The operation is regarded under Venezuelan law as a direct attack on state sovereignty and an act of occupation.

- Constitution of a Crime Against the State: Foreign intervention falls within the category of crimes such as coup d’état, overthrow of the constitutional order, and crimes against national independence.

PRECEDENT VALUE AND IMPLICATIONS FOR THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM

The military operation carried out by the United States in Venezuela, resulting in the forcible apprehension of a sitting head of state, is widely regarded as a precedent-setting development that affects not only bilateral relations but also the foundational norms of the international system and the established principles governing the use of force. This intervention has reopened debates surrounding the legal and institutional balance that states have long sought to preserve in international relations.

Erosion of the Principle of Head of State Immunity

Under international customary law and established diplomatic practice, sitting heads of state enjoy personal immunity from the jurisdiction of foreign states. By forcibly capturing a head of state through the direct use of military force, the United States has created a powerful example suggesting that such immunity may be bypassed in practice.

This development carries the risk that other states may, in the future, define foreign leaders as “criminal actors” under similar justifications and pursue unilateral interventions. While the erosion of immunity may provide greater operational latitude to powerful states in the short term, it risks undermining the security of political leadership worldwide in the long term.

The Legalization of the Use of Force Debate

The attempt to justify the operation on the basis of criminal investigations and federal indictments represents a striking example of the framing of military force as a legal enforcement tool. This approach stands in direct tension with the United Nations Charter system, which was designed to strictly limit the use of force.

If states begin to regard domestic criminal proceedings as sufficient grounds for military intervention within the territory of another sovereign state, this could lead to the erosion of collective security mechanisms and the selective application of international law.

Unilateralism and the Erosion of Collective Security

Because the intervention was conducted without authorization from the United Nations Security Council, it constitutes a clear example of unilateral use of force. This development risks further weakening the principle of collective security and reinforcing a system in which de facto power superiority overrides established legal norms.

The erosion of collective security disproportionately affects small and medium-sized states by reducing predictability within the international system, increasing security anxieties, and deepening dependence on alliances.

Consequences for Great Power Competition

The precedent-setting nature of the operation is being closely observed within the context of great power rivalry. Actors such as Russia and China may interpret this intervention as a reference point for their own security doctrines. This raises the risk that the concept of “legally justified military intervention” may be replicated across different regions.

In this respect, the operation should be understood not merely as a Latin American case, but as one carrying the potential for dangerous ripple effects in regions of heightened tension such as the Asia-Pacific, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East.

Overall Assessment from the Perspective of the International System

In conclusion, beyond any short-term strategic gains, the U.S. operation in Venezuela constitutes a precedent capable of leaving lasting marks on the normative structure of the international system. The blurring of boundaries between state sovereignty, immunity, use of force, and jurisdiction carries the risk of rendering the international order more unpredictable and fragile.

For this reason, the intervention should be assessed not only within the specific contexts of Venezuela and the United States, but also as a critical turning point for the future of international law and systemic stability.

CONCLUSION

The military operation carried out by the United States in Venezuela and the subsequent apprehension of President Nicolás Maduro constitutes a multi-layered and exceptional case from the perspectives of international relations and international law. The intervention reflects an approach in which military methods, criminal law justifications, and strategic objectives are intertwined, thereby presenting a model that differs from conventional forms of interstate use of force.

An examination of the sequence and implementation of the operation indicates that the process was conducted in a pre-planned, coordinated, and time-sensitive manner. While the reasons put forward by the United States were grounded in counter-narcotics efforts, national security concerns, and ongoing federal criminal cases, significant disagreements emerged at the international level regarding the legal validity of these justifications. In particular, the absence of authorization from the United Nations Security Council has positioned the operation as a central point of debate concerning the prohibition on the use of force and the principle of state sovereignty.

International reactions demonstrate the lack of a common and uniform approach within the global system toward interventions of this nature. Whereas some states supported the operation, a substantial number openly condemned it and emphasized that it constituted a violation of international law. This divergence has once again exposed persistent structural challenges related to the normative coherence and enforcement capacity of the current international order.

From a legal assessment perspective, the operation has been subject to differing—and at times conflicting—interpretations under international law, U.S. domestic law, and Venezuelan domestic law. Within the framework of international law, the principles of sovereignty, the prohibition of the use of force, and the immunity of heads of state come to the forefront. In the context of U.S. domestic law, debates have centered on executive authority, federal criminal investigations, and the balance between Congress and the presidency. From the standpoint of Venezuelan domestic law, the intervention has been regarded as a violation of the constitutional order and national sovereignty.

Finally, the precedent value of this operation carries the potential to generate long-term and systemic consequences extending beyond the immediate crisis. Issues such as the status of heads of state, the boundaries between domestic and international law, and the normalization of unilateral use of force are likely to shape future cases of a similar nature. In this respect, the Venezuela case serves as a significant reference point for understanding how the existing rules of the international system are interpreted and how they may evolve in the future.

-

The Strategic Importance of Think Tank Diplomacy in the Uyghur Issue

The Uyghur issue is no longer merely a human rights topic; it has become a global case that tests the norms, legal capacity, and moral consistency of the international system. An issue of this scale and complexity cannot be managed through individual reactions or temporary agendas, but rather through institutional, sustainable, and strategic frameworks of thought.

It is precisely at this point that the role of think tank institutions becomes decisive.

Think tanks are non-state actors that nevertheless feed state-level strategic reasoning. They produce policy, shape narratives, guide decision-makers, and construct legitimacy frameworks in the international public sphere. For the Uyghur cause to be defended effectively and sustainably at the global level, institutions operating in this field must go beyond conventional report-writing and establish multi-layered strategic networks.

In this context, Center for Uyghur Studies is not merely a research center; it holds the potential to become an academic, analytical, and political legitimacy hub for the Uyghur issue. However, for this potential to be fully realized, the institution must be actively and institutionally integrated into the global think tank ecosystem.

The key reality here is clear: the Uyghur issue advances not through statements of goodwill, but through institutionalized and sustainable cooperation.

Building a Global Think Tank Network: Where to Begin?

At this stage, the first strategic step to be taken is clear. The Center for Uyghur Studies must sign formal strategic partnership agreements with think tank institutions around the world, without discrimination by country and without confining itself to specific regions, political blocs, or alliance structures.

These partnerships should not be symbolic. On the contrary, they must include concrete outputs such as joint working mechanisms, information and data sharing, and collaborative report production.

Through such a network, the Uyghur dossier would cease to be the voice of a single institution and instead become a shared agenda of numerous international think tanks. This would render the issue both stronger and more resilient.

Joint Production: From Visibility to Depth

The second phase is not merely about articulation, but about producing together. The international system gives far greater weight to jointly authored, documented, and interdisciplinary knowledge production than to individual statements.

For this reason:

- Joint reports should be produced in collaboration with international think tanks. These reports should address not only human rights violations but also forced labor, supply chains, international law, security, and geopolitical implications.

- Through joint conferences and roundtable discussions, the Uyghur issue should be brought into the analytical space of multiple disciplines.

- Beyond digital content, printed publications and academic compilations should be produced in order to build a lasting institutional memory.

Historic Responsibility and Leadership

The natural responsibility for this entire process rests on the shoulders of Abdulhakim Idris. He is not merely an advocate; through decades of experience, he has repeatedly demonstrated his analytical thinking capacity and strategic intuition.

What is expected here is not merely the articulation of the Uyghur issue. The true expectation is the ability to transform this issue into a permanent agenda item within the international think tank ecosystem.

This is not an easy task. However, history shows that major causes have critical turning points. And those moments require strong institutional leadership.

The analytical intelligence, networking capacity, and ability to correctly interpret institutional language that Abdulhakim Idris possesses can elevate the Center for Uyghur Studies into a permanent and taken-seriously actor within the global think tank landscape.

-

From Associations to Statecraft: The New Threshold of the Uyghur Diaspora

Today, the Uyghur diaspora stands at a historical threshold. This threshold is not merely the beginning of a new phase of struggle; it is the gateway to a new mindset, a new institutional ambition, and ultimately a new level of statecraft. The issue is no longer limited to existence, narration, or visibility. The real question is this: what kind of political actor can be built and sustained.

Until now, the Uyghur cause in the diaspora has been carried largely through associations, foundations, and volunteer platforms. The historical role of these structures cannot be denied. The preservation of identity, the documentation of mass abuses, the awakening of public opinion, and the continuity of the human-rights agenda have been possible thanks to these efforts. Yet one truth has become impossible to ignore: association-based activism was a beginning, not the destination.

The Limits of the Association Model

By their nature, associations tend to be defensive. They react, they respond, but they rarely generate strategy. They do not create law, shape policy, or design a durable architecture of power. More importantly, association-based models often remain fragmented; they can become dependent on individuals and struggle to produce institutional memory that outlives personalities.

The challenges facing the Uyghur diaspora today, however, are now issues of state-level scale:

- Systematic forced labor

- A coercive machinery that has penetrated global supply chains

- Acts that constitute serious crimes under international law

- A people’s fate treated as a bargaining chip among great powers

Responding to this landscape with the reflexes of conventional civic activism is understandable but it is not sufficient.

What Statecraft Means—Not a State Fantasy

What is meant here by “statecraft” is not romantic flag and border rhetoric. It is not armed struggle, nor imaginary declarations of independence. Statecraft is the capacity to:

- Read the international system

- Analyze power balances

- Use law as an instrument

- Produce diplomacy

- Ensure inter-institutional coordination

- Set long-term goals

A people is taken seriously only to the extent that it can develop these capacities. The most critical dilemma of the Uyghur issue today is this: it is morally right, yet too often strategically underpowered.

Giving Birth to a Political Actor from the Diaspora

A new task now stands before the Uyghur diaspora: to evolve from civil society into a political and institutional actor.

This transformation requires breakthroughs in the following areas:

Strategic research centers (think tanks):

Professional structures capable of addressing the Uyghur issue not only through moral language, but also through geopolitical and economic analysis (Uyghur Research Center, Uyghur Academy).International legal units:

Specialized teams focused on universal jurisdiction, forced-labor litigation, sanctions mechanisms, and supply chain accountability cases (cases filed in Argentina, Türkiye, France, and the United Kingdom).Institutional diplomacy networks:

Structures able to engage not merely with “states,” but with state systems parliaments, bureaucracies, and international organizations.Central coordination:

A high-level umbrella that synchronizes rather than fragments Uyghur structures across different countries (World Uyghur Congress).This is not a matter of “one leader.” It is a matter of institutional intelligence.

From a Victim Identity to a Foundational Identity

In the international system, the Uyghur people are too often seen only as victims. Yet victimhood alone does not generate political power. International politics is unforgiving: it makes room not for the righteous, but for the organized and the rational.

For this reason, the Uyghur diaspora must redefine itself:

- Not merely as a community under oppression, but

- as a political actor with a credible vision of the future.

Without this transformation, neither meaningful pressure on China nor a durable place in the global system can be secured.

Final Word: History Does Not Wait

Time is not limitless for any diaspora. Institutional capacity that is not built today cannot be easily repaired tomorrow. Every delay risks the issue becoming normalized then slowly dissolving into the noise of the global agenda.

Association-based activism is an honorable chapter of the Uyghur struggle. But a new chapter must now be opened.

Its title is clear: the transition from associations to statecraft.

And this transition is not a preference—it is a historical necessity.

-

Venezuela Tanker Crisis: Key Legal Questions Raised by the U.S. Intervention at Sea

The United States’ seizure of a Venezuelan oil tanker off the country’s coast has immediately raised tensions in the region. Incidents like this often drift into a space where political rhetoric intensifies while legal debates get overshadowed. Yet this is precisely the kind of issue that requires a calm and deliberate examination of international and maritime law.

Washington justifies the operation by referring to its own sanctions regime; Caracas, in turn, frames the act as “international piracy.” Between these two competing narratives lies a more uncomfortable truth: powerful states tend to apply their own normative frameworks as though they are universally binding. There’s an old but accurate observation in international relations: we see the law of the powerful more often than the power of the law. This case is not much different.

International Law and the Question of JurisdictionA state’s authority to seize a commercial vessel on the high seas is extremely limited. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) emphasizes the status of the high seas as “the common heritage of humankind,” restricting states’ ability to exercise enforcement powers. Piracy, slave trading, unauthorized broadcasting, or situations involving stateless vessels constitute narrow exceptions.

From this standpoint, even if the United States relies on its domestic laws and sanctions, such measures do not automatically create legitimacy under international law. Sanctions enacted unilaterally lack universal enforceability. No state—especially one already in a politically adversarial relationship—is obligated to recognize another state’s domestic sanctions regime. In this sense, a military seizure of a tanker falls into a legal space that is not merely gray but rather notably dark.

Power Projection and Creating Facts at SeaBeyond being a conventional example of power projection, the operation reflects a broader strategy of creating “facts on the water.” By targeting a vital artery of Venezuela’s economy—its oil transport—the United States sends a subtle message to other regional actors: “Our sanctions are not just policy statements; they can and will be enforced.”

Remaining entirely neutral here feels unrealistic. The international system maintains stability only to the extent that the rule of law remains intact. Once states begin interfering with each other’s commercial vessels with increasing ease, the precedent becomes dangerous. Today it’s a Venezuelan tanker; tomorrow it could be another nation’s vessel. Where exactly will the line be drawn?

Conclusion: Every Step Away from Law Expands UncertaintyThis incident is not merely another chapter in the long-running tensions between Washington and Caracas; it is a snapshot of a global environment in which international law is repeatedly tested. As states rely on domestic legal rationales to justify actions affecting foreign assets, the international legal order weakens and systemic uncertainty grows.

Staying impartial does not require suppressing legitimate concerns. Any unease expressed here stems not from affection for Venezuela or hostility toward the United States, but from a broader worry: actions that erode the framework of international law ultimately make the entire global order more fragile.

At the end of the day, the question is simple: Will power prevail at sea, or will the law? The answer affects far more than this single incident—it affects all of us.

-

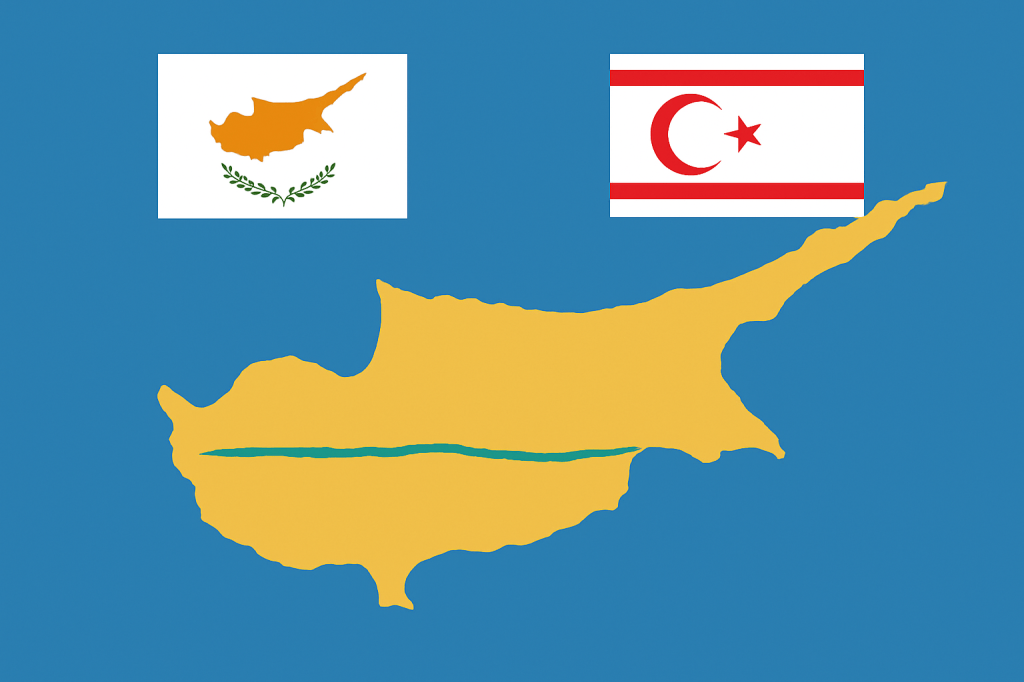

A Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Cyprus’ Reunification

Historical Background and the Evolution of Negotiations

After the intercommunal clashes that began in 1963 and the subsequent de facto division of the island, the UN-controlled Green Line in central Nicosia has continued to serve as a buffer zone separating the north and south of the island since 1974. Although the Republic of Cyprus was established in 1960 as a bi-communal partnership state, this arrangement did not last long. In 1963, following unilateral attempts by the Greek Cypriot leadership to amend the constitution and the eruption of armed clashes known as Bloody Christmas, the partnership state effectively collapsed; Turkish Cypriots were excluded from state institutions. The island-wide escalation of violence and Greece’s interventions aimed at Enosis (union with Greece) laid the groundwork for Turkey’s intervention. On 15 July 1974, when the Greek junta in Greece staged a coup in Cyprus and Makarios was overthrown in an attempt to declare Enosis, Turkey launched a military operation on 20 July 1974, invoking the Treaty of Guarantee. As a result of the Cyprus Peace Operation, which took place in two phases, 37% of the island came under Turkish control and the current de facto boundaries were drawn. Subsequently, under UN supervision, a population exchange was implemented in 1975, whereby Turks were concentrated in the north and Greeks in the south; approximately 120,000 Greek Cypriots resettled in the south and 65,000 Turkish Cypriots in the north. This separation laid the foundations for the two separate administrations on the island.

After 1974, efforts to resolve the Cyprus issue continued uninterruptedly under UN auspices. In the 1977 and 1979 High-Level Agreements, the principle of a bi-communal, bi-zonal federal solution was adopted. However, on 15 November 1983, the Turkish Cypriot side declared that, exercising its right to self-determination, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) had been established. Although this declaration of independence was not recognized internationally, Turkish Cypriots announced that they would continue to advocate a federation model in the negotiations. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, various UN plans (most notably the 1985–86 Draft Framework Agreement, the 1992 Ghali Set of Ideas, etc.) were presented to the sides, but each time they failed due to disagreements. Toward the end of the 1990s, the EU accession process of the Republic of Cyprus introduced a different dynamic into the search for a solution; it became apparent that despite the division of the island, the southern part of Cyprus could enter the EU on behalf of the whole island.

In the 2000s, hopes for a solution reached their peak. The comprehensive Annan Plan, prepared through the efforts of UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, was put to simultaneous referenda on both sides on 24 April 2004. Turkish Cypriots strongly backed the plan with a 64.9% (65%) “Yes” vote, while Greek Cypriots rejected it with 75.8% (76%) “No”. As reunification failed due to the Greek Cypriot rejection, the international community subsequently admitted the Republic of Cyprus (the Greek Cypriot government) as a full member of the European Union on 1 May 2004 on behalf of the entire island. This development reinforced among the Turkish Cypriot people—who had voted “yes” for a solution—the sentiment that the promises made to them had not been fulfilled; isolation and embargoes continued. The rejection of the plan consolidated the de facto division of the island and deepened the trust gap between the two sides.

In 2008, negotiations between the leaders Talat and Christofias restarted and achieved some convergences, but could not produce a comprehensive settlement. Most recently, the federal negotiations revived in 2015 by the leaders Akıncı and Anastasiades culminated at the Crans-Montana Conference in Switzerland in June 2017. With the participation of the guarantor states Turkey, Greece, and the United Kingdom, this conference was considered one of the closest moments to a solution. During the conference, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres presented a “package solution” proposal covering six chapters, including security and guarantees. However, the Greek Cypriot side adopted an uncompromising stance, insisting on “zero troops, zero guarantees from the first day,” particularly regarding Turkey’s military presence and the guarantee system, and even refused balanced proposals put forward by the UN. Despite the flexible and constructive approach of the Turkish Cypriot side, no agreement was reached on critical issues; in July 2017, Guterres announced that the conference had ended in failure. The Crans-Montana talks represented a turning point in the search for a federal solution, and the failure to reconvene a formal negotiation table afterwards brought new alternatives to the agenda.

After 2017, the Cyprus peace process entered a prolonged pause. In October 2020, with the election of Ersin Tatar as President of the TRNC, a new vision was put forward: the argument that the federation model had been exhausted, coupled with a formal proposal for a two-state solution on the basis of sovereign equality. Turkey likewise declared that it embraced this paradigm. Then-Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu stated that “we cannot embark on an open-ended adventure for a federation that will not yield results,” emphasizing that different solution options should be prioritized. At the informal 5+1 meeting held in Geneva in April 2021 under the UN framework, the Turkish side officially presented, for the first time, a detailed two-state vision and put forward as a precondition the recognition of the TRNC’s equal international status. However, the Greek Cypriot side and the international community rejected this thesis on the grounds that it contradicts UN resolutions. In 2022, Turkey reiterated its stance at the highest level by calling on the world to recognize the TRNC during the UN General Assembly. All these developments indicate that we have entered a period in which the negotiation parameters have fundamentally changed. At the same time, the partial opening of the long-closed Maraş (Varosha) area to civilian use by the TRNC in October 2020demonstrated that the status quo is now being challenged by different moves.

At this point, although the Cyprus issue remains unresolved, over 60+ years the sides have gone through numerous plans, countless meetings, and many mediators. Historically, the collapse of the 1960 partnership arrangement, the de facto partition in 1974, the rejection of the Annan Plan in 2004, and the failure of Crans-Montana in 2017 stand out as key turning points in reunification efforts. In light of these experiences, the question now on the agenda is whether the negotiation parameters will change. The quest for a solution to Cyprus’s future is being reshaped by lessons drawn from history.

Current Reunification Scenarios and Solution Models

Several scenarios have long been discussed for resolving the Cyprus issue. The most frequently mentioned models are as follows:

Bi-Communal Federation: The established solution model, defined by UN Security Council resolutions, foresees the establishment of a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation based on political equality on the island. Under this model, constituent states in the north and south would have their own autonomous administrations, while in external relations the united Cyprus state would be represented under a single sovereignty. The federation model has been presented in theory as the fairest balance, as it guarantees both the political equality of the two peoples and a certain degree of separate self-governance. Indeed, the UN and the international community have recognized a federation as the basis for a solution since 1977. However, in decades of federation negotiations, the sides could not reach agreement on critical issues (such as power sharing, rotating presidency, territorial arrangements, etc.); in particular, the Greek Cypriot desire for strong central government powers and the Turkish Cypriot sensitivity over political equality have made it difficult to implement this model. At this stage, although the federation officially remains on the table, its feasibility has become a matter of debate due to mutual mistrust.

Confederation: This model envisions two separate sovereign states forming a loose higher-level partnership through a framework agreement. In practice, it implies the presence of two independent states, but coordinated through certain joint organs. The confederation option was proposed notably by the Turkish Cypriot leadership in the 1990s under the formula of “cooperation between two sovereign states.” In this scenario, the existing TRNC and the Republic of Cyprus would recognize each other as separate states, and if this status were accepted internationally, a partnership would be established through inter-state agreements. Confederation has sometimes been brought up by the Turkish side as an alternative to the “exhausted federation”, but the Greek Cypriot side rejects it on the grounds that it would mean permanent partition. Furthermore, for a confederal solution to materialize, the TRNC would first need to be recognized or the Greek Cypriot side would need to accept a sharing of sovereignty; therefore, this scenario is seen as distant in practice.

Two Separate States (Partition): This scenario envisages the permanent consolidation of the division already in place, with two independent states on the island, one Turkish in the north and one Greek in the south. The Turkish Cypriot side and Turkey have increasingly emphasized that a solution is possible only on the basis of two sovereign states. Especially after the failure of federal initiatives in 2017, the “two-state solution” thesis has gained strength. Surveys also show that support for this option among Turkish Cypriots has increased: in a survey conducted in the TRNC in January 2020, 81.3% of Turkish Cypriots stated that they supported two separate states, while those favoring federation remained at 10%. From the Turkish side’s perspective, a two-state option is a realistic approach and a reflection of the existing de facto situation, as generations in the TRNC have lived within this order. However, in terms of international law and politics, it is the most challenging scenario. UN resolutions emphasize the principle of single sovereignty in Cyprus and do not recognize the structure in the north. The European Union has also stated at the highest level that it will “never accept a two-state solution”. For the Greek Cypriot side, too, dividing sovereignty is a red line. Therefore, the two-state formula, whose international recognition is seen as nearly impossible, would be less a negotiated solution and more a “de facto acceptance of the current situation”. Even if Turkey’s strong support and potential recognition moves by other countries were forthcoming, they might not suffice to alter the status quo; indeed, UN Security Council Resolutions 541 and 550 of 1983 declared the TRNC’s independence legally invalid. In sum, although the two-state option is present on the table as a view, its implementability in the international context is extremely low.

Apart from these scenarios, some authors propose hybrid formulas such as a “loose union under the EU umbrella” or a “decentralized federation.” For instance, the new Greek Cypriot leader Nikos Christodoulides has argued that a highly decentralized federation could address some of the Turkish side’s concerns. Ultimately, debates around the solution model focus on the question “which model is worth negotiating?”. Unless a common ground can be found between the sides, no scenario will be implementable. As of today, the Greek Cypriot side officially remains aligned with the federation line, while the Turkish side insists on the two-state thesis. For this reason, the core issue in Cyprus is to reach consensus on a shared vision.

The Role of International Actors

The Cyprus issue is a multi-faceted problem that concerns not only the parties on the island but also regional and global actors. In efforts toward reunification, the United Nations, the European Union, Turkey, Greece, the United Kingdom, and other relevant actors play prominent roles:

United Nations (UN): The UN, the primary mediator in the Cyprus issue, has deployed a peacekeeping force (UNFICYP) on the island since 1964 to help maintain security. Since 1968, the “Good Offices Mission” of the UN Secretary-General has hosted and facilitated negotiations. The UN’s solution parameters are based on a bi-communal, bi-zonal federation grounded in political equality. Within this framework, comprehensive plans (such as the 1992 Ghali Ideas, the 2004 Annan Plan, and the 2017 Guterres Framework) have been prepared, and successive Secretaries-General have tried to secure convergence between the sides. However, most recently, a diplomatic envoy appointed by Secretary-General Antonio Guterres to hold contacts on the island in 2023–24 reported that there is no common ground between the parties. The UN has had difficulty narrowing the deep gap between the parties regarding the vision for a solution. Nevertheless, Guterres has continued efforts to bring the sides together in informal formats as of 2025. The UN maintains its mediation while remaining committed to the parameters set by Security Council resolutions, and at the same time continues its mandate to preserve stability on the island.

European Union (EU): With the accession of the Republic of Cyprus to the EU in 2004, the Union became a significant dimension of the problem. While the southern part of Cyprus became an EU member, the application of the EU acquis in the northern TRNC was temporarily suspended. The EU has for years supported economic development in the north through mechanisms such as the Aid Programme and the Green Line Regulation, aiming at facilitating the integration of the Turkish Cypriot community into the acquis in the event of a solution. EU institutions have clearly expressed their stance in favor of a settlement in the form of a federation. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen emphasized that the EU would “never accept a two-state solution in Cyprus”, indicating that the Union remains firmly united on this issue. In 2023, through efforts by the Greek Cypriot leadership under Christodoulides, the EU signaled its intention to be more involved in the negotiations by appointing a special envoy to the process. In May 2025, the European Commission appointed former Commissioner Johannes Hahn as its Special Envoy for Cyprus, demonstrating its will to enhance its contribution to UN-led solution efforts. In its statement, the EU stressed that the Union remains committed to the goal of reunification of the island, based on UN Security Council resolutions and the EU’s principles and values, and that the solution must be compatible with and sustainable under EU law. In summary, the EU is a key actor in the resolution of the Cyprus issue both through its normative power (e.g., the status of a united Cyprus within the EU) and its incentives (financial aid, the broader dimension of Turkey–EU relations).

Turkey: For Turkey, the Cyprus issue is a “national cause.” As a guarantor of the constitutional order established in 1960 under the Treaty of Guarantee, Turkey intervened militarily in 1974, assuming a role as the protector of the Turkish Cypriots. Since then, through its military presence and financial and political support to the north of the island, Turkey has been a principal actor shaping the de facto situation. In the early 2000s, Turkey strongly supported the Annan Plan, thereby adopting a solution-oriented stance and even encouraging the Turkish Cypriot side to approve the plan. However, after the Greek Cypriot rejection of the referendum and especially after the failure at Crans-Montana in 2017, Ankara’s position underwent a transformation. Today, Turkey conditions any solution on the recognition of the sovereign equality of the TRNC and argues that the federation model has been exhausted. President Erdoğan, in speeches before the UN General Assembly in 2022 and 2023, called on the international community to recognize the TRNC, thereby putting the two-state vision on the global agenda. Turkey also considers its strategic interests in the Eastern Mediterranean (hydrocarbon exploration, maritime jurisdiction areas) as part of the Cyprus equation. On the security front, Turkey continues to regard the presence of Turkish troops on the island as vital for the security of the Turkish Cypriots and opposes the abolition of the 1960 guarantee system. Indeed, the guarantee issue was the most critical obstacle at Crans-Montana in 2017. Although Turkey’s vision for a solution in Cyprus lacks international acceptance, it remains decisive in terms of the de facto balance on the island. As the “motherland,” Turkey provides direct financial support to the TRNC economy and strengthens integration through energy and infrastructure projects. Ultimately, for any solution in Cyprus to be implementable, Turkey’s consent and active support are indispensable.

Greece: Due to historical, cultural, and political ties, Greece is the closest supporter of the Greek Cypriot side. As a guarantor of Cyprus’s independence under the 1960 arrangements, Greece became part of the tragedy in Cyprus through the Greek junta’s coup attempt in 1974. Following the restoration of democracy, Greek governments pulled the country toward a more international law-based stance on Cyprus. Officially, Greece declares that it supports the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Republic of Cyprus and that the solution in Cyprus should be a federation within the UN parameters. While Athens tries not to be a direct party at the negotiation table and leaves the leadership of the process to the Greek Cypriots, it has played active roles on security and guarantees in particular. For example, at the Crans-Montana Conference in 2017, the Greek foreign minister stated that the 1960 guarantee system was obsolete and should be abolished. While the Greek armed forces have not been officially present in Cyprus since 1974, “the protection of Hellenism in Cyprus” remains an important theme in Greek foreign policy. In recent years, Greece has sought to solidify Cyprus’s status through energy and defense cooperation frameworks in the Eastern Mediterranean with Egypt, Israel, and the Greek Cypriot administration. Greece’s positions within the EU and NATO also strengthen its hand vis-à-vis Turkey over the Cyprus issue. Overall, Athens wants a solution in which Turkish troops leave the island, the guarantee rights are abolished, and the Greek Cypriot side’s security concerns are addressed. In line with these goals, Greece acts in full alignment with the Greek Cypriot side in the Cyprus negotiations. It should also be remembered that any eventual settlement will require ratification by the Greek parliament; hence Greece is an integral actor in the solution equation.

United Kingdom: As the island’s former colonial ruler, the UK occupies a unique position in Cyprus. Under the 1960 Agreements, it retained sovereign base areas on 3% of the island’s territory, namely Akrotiri and Dhekelia. The UK, together with Turkey and Greece, is a guarantor state of Cyprus’s independence and constitutional order. Regarding a solution, the UK officially supports UN efforts and declares its commitment to the principle of a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation. London pursues a policy of balanced friendship towards both sides on the island, but due to its strategic interests in the Eastern Mediterranean (the continued presence of its military bases, regional stability, migration flows, etc.), it favors a manageable status quo. In the period of the Annan Plan in 2004, the UK even proposed to cede part of the land within its sovereign base areas to a united Cyprus as a contribution to a solution (a proposal that did not come into effect because the plan was rejected). In the latest negotiations, the UK participated in the talks as a guarantor but played a more background role. Although the UK has left the EU, it stresses that a solution in Cyprus would be in everyone’s interest. For the UK, reunification would offer economic and political opportunities, such as establishing special relations with a united EU-member Cyprus and expanding trade ties with the Turkish side. The UK also supports confidence-building measures between the two communities (for example, demining projects and cultural heritage preservation). In short, while the UK continues to voice support for a “fair and lasting settlement,” it will be attentive to ensuring that any agreement preserves its own military and geopolitical interests. Even if the guarantee system is abolished, the status of the British bases will remain a separate topic of negotiation on the table.

Other Actors: The Cyprus issue has attracted the interest of several major powers, especially the US and Russia. The United States has emphasized throughout the Cold War and beyond the importance of maintaining balances in Cyprus in favor of NATO. It actively supported the Annan Plan in 2004 and took initiatives to alleviate the isolation imposed on Turkish Cypriots after the referenda. Today, the US strengthens its relations with the Republic of Cyprus to counter Russian and Chinese influence in the Eastern Mediterranean; lifting the arms embargo on the south in 2022 is an indicator of this trend. Washington states that it would support any formula that both communities agree upon, yet in practice it backs the UN’s stance favoring federation. Russia, on the other hand, has traditionally been closer to the Greek Cypriot side and has opposed changes to the solution parameters in the UN Security Council. Moscow may be uncomfortable with the increased Western influence on the island and therefore tends to be cautious about radical moves on the Cyprus issue. Russian capital and citizens have long occupied a notable place in the economy of the south, which may incline Russia toward a continuation of the status quo. The permanent members of the UN Security Council (the US, Russia, the UK, France, and China) have for years adopted similar resolutions on Cyprus, emphasizing the island’s territorial integrity, the bi-communal federation principle, and the non-recognition of the TRNC. At the regional level, EU member states and neighboring Middle Eastern countries (such as Israel and Egypt) can also be considered indirect actors due to the impact of Cyprus’s stability on their interests. In summary, the reunification of Cyprus involves a multi-layered diplomatic chessboard, where the positions of international actors sometimes facilitate efforts for a solution and sometimes complicate them.

Social Tendencies and Reactions

In the Cyprus issue, the attitudes of political leaders are as important as the tendencies of the two peoples on the island regarding reunification. Over the years, the decades-long separation between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots has shaped public perceptions of one another in opposing ways. However, polls and field research show that both communities have not completely closed the door to a peaceful future:

Public Opinion Trends: The fact that the two communities voted in opposite directions in the 2004 Annan Plan referenda (Turkish Cypriots 65% “Yes,” Greek Cypriots 76% “No”) starkly exposed the trust gap between them. Yet there has been some rapprochement in the intervening years. Particularly since the opening of the crossing points in 2003, everyday interactions have increased, fostering curiosity and empathy among the communities. A comprehensive public opinion survey conducted in 2020 revealed that there is still a live desire for a federal solution on both sides: 66.5% of Greek Cypriot respondents and 63.6% of Turkish Cypriot respondents declared that they aspire to a united federal Cyprus. These significantly high percentages are important in showing that, at a time when official rhetoric has hardened, the peoples remain basically open to peace. The same study also found that the solution package proposed by Secretary-General Guterres in 2017, designed to balance the sensitivities of both sides (particularly on security guarantees and political equality), could be supported by 84% of Greek Cypriots and 60% of Turkish Cypriots. This suggests that a properly designed compromise could enjoy broad public acceptance.

Mistrust and Psychological Barriers: Of course, optimistic survey data do not mean that deep-rooted prejudices and fears have been fully overcome. Both communities still carry the legacy of past traumas. Among Greek Cypriots, there is widespread concern about the permanent presence of the Turkish military and the risk of becoming a minority in a reunited state. For many Greek Cypriots, the “1974 trauma” remains fresh and trust in the Turkish side is scarce. On the other hand, Turkish Cypriots have not forgotten the attacks between 1963 and 1974 and the Maronite–Greek blockades; they fear “if we share power again, will we experience the same things?” This historical spiral of mistrust has been reinforced by both the media and education systems. On both sides, school curricula long contained narratives that demonized the “other.” As a result, there are significant sectors that view the idea of reunification with suspicion. Looking specifically at younger generations, an interesting divergence emerges: a considerable portion of Turkish Cypriot youth communicate with their Greek peers via social media, whereas this rate is very low among Greek Cypriot youth. According to one study, 41% of Turkish youths reported interacting with Greek Cypriots on Facebook at least once a month, while this rate is just about 8% among Greek youths. This indicates that Turkish Cypriot society has become more open to contact and dialogue, whereas alienation appears stronger among the younger generation in the Greek Cypriot community. Population and welfare disparities also create psychological barriers: some circles in the south say they do not want to bear the economic burden of the poorer north if reunification occurs, while on the Turkish Cypriot side there are concerns that if reunification happens, their freedoms might be restricted.

Bi-Communal Contacts and Civil Society: Since the opening of the crossing points in 2003, there have been millions of crossings between the two sides over more than 20 years; people visited each other’s villages and towns, and established day-to-day interactions. These contacts have helped break down some prejudices. Academic studies demonstrate that increased face-to-face contact reduces fears about the other side and increases support for a settlement. In fact, the Bi-Communal Technical Committees, set up after 2008, implemented several small-scale confidence-building measures in areas such as health, culture, environment, and crisis management, achieving concrete successes like joint mine clearance and the restoration of cultural heritage sites. Moreover, civil society initiatives continue efforts to build public support for reunification. Peace activists from both sides organized joint actions on platforms such as “Unite Cyprus Now”; young people in 2011 set up a joint camp at the Ledra/Lokmacı crossing point under the name “Occupy Buffer Zone” to symbolically demonstrate their demand for a solution. Although such initiatives have not mobilized mass participation, they have resonated in the media and sent a grassroots message to political leaders. In the Turkish Cypriot community, there was particularly strong desire for a solution in the 2000s; their 65% “Yes” to the Annan Plan was a clear indication of this. Even though isolation did not end after the plan, Turkish Cypriots maintained their hope of integrating with the outside world. In recent years, this desire has somewhat diminished due to the growing political and economic influence of Turkey and the strengthening two-state discourse, yet a significant segment of the population continues to crave inclusion within international law. In the Greek Cypriot community, during the Annan Plan era, the “No” campaign argued that “a better solution is possible.” Over time, however, the Greek Cypriots have enjoyed the advantages of the status quo. The sense of prosperity and security brought by EU membership reduced the urgency of a solution. On the other hand, among the Greek Cypriot displaced population (those who lost their homes in 1974), frustration and longing have grown. Research indicates that many displaced Greek Cypriots, who once supported “no” in the belief that a better solution would come, now think that this was a mistake and are more open to compromise. Thus, over time, the view “we should have made peace while we had the chance” has become widespread among generations who lost their homes in 1974.

Intra-Community Political Divisions: There are disagreements about reunification within each community as well. On the Turkish Cypriot side, left-wing parties (such as CTP) advocate a federation and reunification within the EU, whereas the right-nationalist wing (UBP, HP, etc.) supports a two-state solution or, at the very least, deeper integration with Turkey. With the election of Ersin Tatar in 2020, the official policy of the TRNC shifted fully toward a two-state model, yet approximately half of the society still consists of people who favor a federation or some form of convergence—this can be inferred from the nearly split vote between the two candidates in the 2020 election. On the Greek Cypriot side, similarly, center-left parties (like AKEL) tend to favor a solution, while center-right (DISY) remains cautious and the far-right (ELAM) is openly anti-solution. Although Nikos Christodoulides, elected president in 2023, has introduced new ideas for a solution (such as a more active role for the EU), he essentially follows a nationalist line that leans toward a unitary-state perspective. Thus, within the Greek Cypriot community, one camp says “we must reunify under any circumstances,” while another insists “never, as long as the Turkish army is on the island.” These internal balances can restrict leaders’ room for maneuver. For instance, one of the factors limiting Anastasiades from showing more flexibility at Crans-Montana in 2017 was the likely backlash at home. Similarly, criticism that Akıncı “gave too many concessions” contributed to his failure to be re-elected in 2020.

In summary, the hearts and minds of the two peoples are crucial in the matter of Cyprus’s reunification. Although there is a substantial segment on both sides that keeps hope for peace alive, mutual mistrust remains a reality. At the societal level, improving perceptions of the “other” is essential for a possible agreement to pass referenda. Keeping channels of dialogue open between the two communities, and encouraging younger generations to get to know each other, are necessary. Civil society efforts and everyday interactions offer small but meaningful rays of hope when politics is deadlocked. Reunification can only happen when a significant majority of ordinary people on the island say “enough is enough, we want lasting peace.” Although that threshold has not yet been reached, public opinion trends show that the status quo is not seen as a permanent destiny.

Legal, Economic, and Security Dimensions

The establishment of a reunited Cyprus is not only a matter of political will; it also depends on solving numerous issues in legal, economic, and security domains. From property and territorial arrangements to citizenship statuses, from security guarantees to economic convergence, many structural issues require deep negotiation:

The Property Issue: One of the most intricate dimensions of the Cyprus problem is the matter of property rights over the homes, lands, and businesses left behind by tens of thousands of people who were displaced on both sides as a result of events between 1963 and 1974. When two homogeneous regions were created by the 1975 population exchange agreement, with 120,000 Greeks relocating to the south and 65,000 Turks to the north, abandoned properties came under the control of the new authorities. There have been longstanding claims over properties belonging to Greeks in the north and Turkish properties and villages in the south. Following individual property cases brought to the European Court of Human Rights (e.g., the Loizidou case), mechanisms such as the Immovable Property Commission in the north were established to provide compensation and limited restitution; yet these are only temporary measures. In comprehensive settlement negotiations, the property chapter has been among the toughest to resolve. The Annan Plan proposed complex formulas of compensation, restitution, and exchange; similarly, user rights and other mechanisms were discussed at Crans-Montana. Today, the property issue continues to trigger legal tensions. As some Greek Cypriot properties in the TRNC have been sold to third parties, Greek courts in the south have started issuing arrest warrants against foreign individuals involved in such transactions. In 2023–2024, several foreign businesspeople were arrested for this reason, prompting the TRNC authorities to adopt protective measures for their nationals who were involved in sales of Greek properties. This tension even affected the leaders’ meeting in May 2025; the Turkish side stressed that the Greek courts’ stance undermines the atmosphere of trust. In the event of reunification, resolving the property issue will require creative formulas that do not generate new victims. Most likely, this will involve establishing a compensation fund, balancing restitution and user rights based on certain criteria (for example, giving priority to the return of currently empty areas like Maraş/Varosha). As the property issue is directly linked to human stories, it is crucial for social peace after reunification.

Citizenship and Demography: Another sensitive dimension of the Cyprus problem is the demographic structure and citizenship on the island. After 1974, there was a substantial influx of population from Turkey to northern Cyprus. Today, a significant portion of the TRNC’s population has family roots in Turkey. The Greek Cypriot side regards this as an attempt to “alter the demographic structure through population transfer”, which it considers illegal. It also argues that the Turkish side has thereby strengthened its two-state objective. The Turkish side, however, integrated newcomers from Anatolia into the TRNC in the 1980s and 1990s, boosting its population. Today, the TRNC’s population is estimated at over 300,000 (including citizens and residents), while the Republic of Cyprus has around 900,000 inhabitants. In a solution, the question “which individuals will acquire citizenship of the new united Cyprus” becomes a major negotiation topic. The Annan Plan envisaged that a significant part of the Turkish settlers in the north (around 45,000 people) would receive citizenship of the united state, while the rest could remain under residence status. Similar debates are still relevant today: the Greek Cypriot side wants to limit the number of “settlers” and stop new inflows from Turkey, while the Turkish side emphasizes that people born and raised on the island for 50 years should not be considered foreigners. Hence, a formula of quotas or phased acceptance will likely be needed regarding citizenship. For instance, earlier considered criteria included caps such as “citizens of Turkey should not exceed 10% of the population in the north”. In addition, the status of tens of thousands of Turkish-origin residents in the TRNC who are not TRNC citizens must also be addressed in a settlement. This issue is not just about demography, but also about identity. Within the Turkish Cypriot community, the distinction between “native Cypriots” and “Turkish immigrants” is sometimes felt. In a united future, overcoming these distinctions is key for social cohesion. On the other hand, the statuses of Maronite, Latin, and Armenian minorities living in the south will also be redefined after reunification.

Security and Guarantees: Security is perhaps the most emotionally charged aspect of the settlement question in Cyprus. The 1960 system of guarantees (with Turkey, Greece, and the UK as guarantors) and the Treaty of Alliance allowed the stationing of limited Greek (950) and Turkish (650) troops on the island. However, after 1974, Turkey’s deployment of tens of thousands of soldiers on the island and a de facto balance with Greece created a security paradox. For Greek Cypriots, security means the withdrawal of Turkish troops and the end of unilateral intervention rights. The “zero troops, zero guarantees” formula has broad support in the Greek Cypriot community. For Turkish Cypriots, security means the continuation of Turkey’s guarantee to prevent a recurrence of past events. They respond, “without guarantees, without Turkey’s protection, we will have zero security”. This dilemma was a key obstacle to a settlement at Crans-Montana. The UN’s Guterres Framework proposed an innovative approach to security arrangements: it envisaged ending the guarantors’ unilateral intervention rights from day one and replacing them with an international implementation and monitoring mechanism alongside a phased withdrawal of Turkish troops. Moreover, a new “Security Agreement” involving multi-party guarantees acceptable to both communities was proposed. The Turkish side was, in principle, open to this concept, but the Greek Cypriot side would not sign without a clear timetable that would eventually remove Turkish troops altogether. In a post-settlement environment, security arrangements would likely include the following: an international peacekeeping force (under the UN or EU) stationed on the island for a transitional period; replacement of the current guarantee system with a new multi-party security agreement; and redefined roles for Turkey, Greece, and the UK (for example, consultation and involvement mechanisms without unilateral intervention rights). Another formula would be the inclusion of a revision clause in the agreement, allowing the parties to review security arrangements after a certain period (e.g., 10–15 years). The ultimate goal is to establish a balance in which both communities feel secure. A reunification in which one side feels threatened cannot succeed. Therefore, the issue of security guarantees must be negotiated very carefully with the participation of the guarantor states. In particular, the future of Turkey’s military presence on the island remains a vital concern for the Turkish Cypriot community.